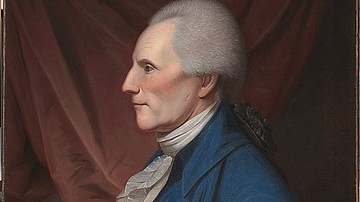

Patrick Henry (1736-1799) was a Virginian lawyer and politician who played a vital role in the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789). Known for his brilliant oration, including the famous Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death speech, Henry served as the first and sixth governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia and is considered a Founding Father of the United States.

Early Life

Patrick Henry was born on 29 May 1736 at Studley Plantation, the Henry family farm, in Hanover County, in the British colony of Virginia. His father, John Henry, was a Scottish immigrant originally from Aberdeenshire, who had come to Virginia in the 1720s and settled in Hanover County in 1732. John Henry quickly became a respected member of the community, working as a planter and mapmaker, serving as a colonel of the militia, and eventually becoming justice of the peace for Hanover County. He married Sarah Winston Syme, a young widow from a prominent Virginian family, with whom he would have nine children; Patrick was the couple's second child.

Henry was educated at a local school until the age of 10, at which point he was pulled out to be tutored by his father, who himself had been well-educated at King's College. Henry was also tutored by his uncle and namesake, Reverend Patrick Henry, an Anglican minister and rector of the Hanover parish, St. Paul's. From his uncle, young Henry learned to be a pious and dutiful Anglican, which he would remain for the duration of his life, even when his outspoken beliefs would later bring him into conflict with the Anglican Church (once the revolution severed American ties with the Anglican Church, Henry became an Episcopalian, the new American equivalent). Henry also occasionally attended Presbyterian services with his mother, where he was exposed to the powerful sermons of the evangelical minister Samuel Davies; it is believed that Davies' passionate speeches, rooted in the religious ideals of the First Great Awakening, influenced Henry's own development as an orator.

Henry grew into a charming, handsome young man, who was fond of music and dancing and never had trouble attracting the attention of young ladies. Yet despite these attributes, Henry had a problem; since he was not his father's eldest son, he did not stand to inherit the family estate under the primogeniture laws of Virginia and therefore had to make his own way in the world. When he was 15, Henry clerked for a local merchant and, a year later, opened his own store with his older brother William, harboring ambitions of becoming a merchant himself. These ambitions were short-lived, however, as the store quickly failed. In October 1754, 18-year-old Henry married 16-year-old Sarah Shelton, whose dowry included a 600-acre farm called Pine Slash as well as six enslaved people. Although this appeared to be a golden opportunity, Henry's career as a planter was just as fruitful as his store-owning venture. The fields of Pine Slash had been exhausted from prior cultivations, and Henry's efforts to clear fresh fields were to no avail. Once the plantation's main house burned down, the frustrated Henry gave up the farm.

The hapless young Henry soon found work as a host at the Hanover Tavern, owned by his father-in-law. Henry was a popular host who amused the tavern's guests by playing the fiddle; it was in this capacity that he met and befriended 17-year-old Thomas Jefferson, who stayed at the tavern several times. But the costs of providing for his rapidly growing family – he and Sarah would ultimately have six children together – required Henry to look for a more substantial source of income. While still working at the tavern, Henry began to study law and, in April 1760, passed the bar. For the next three years, he would work as a lawyer in the Hanover County court, never dreaming that he would soon be thrust into fame.

Lawyer & Revolutionary Beginnings

Henry's rise to fame would occur thanks to a legal and political controversy known as the Parson's Cause. The case revolved around the Two Penny Act, a tax policy passed by Virginia's House of Burgesses that temporarily fixed the price of tobacco at two pennies per pound. This was done because a drought had sharply increased the price of tobacco leaving many Virginians, who often used tobacco notes instead of hard currency, unable to pay their debts. This act angered a vocal minority of Virginia's Anglican ministers (including Henry's uncle), whose salaries were expressed in tobacco and who felt that the price fix was depriving them of their full salaries (inflation had caused the price of tobacco to rise to six pence per pound). The ministers petitioned the king's Privy Council in London to veto the Two Penny Act, which was done. Then, several ministers brought lawsuits to receive the back pay they believed was owed to them.

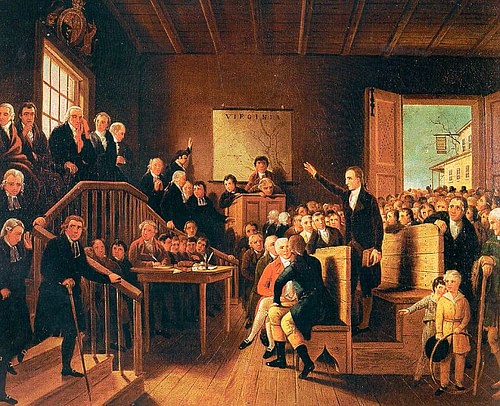

One such lawsuit, brought by Reverend James Maury, was successful, and a jury convened at the Hanover County courthouse on 1 December 1763 to determine the amount of damages that Maury was to be paid. Representing the defendant was 27-year-old Patrick Henry, who was still a relatively new lawyer, unknown outside Hanover County. Rather than haggle with Maury's lawyers over price, as one may have expected, Henry instead launched into an impassioned speech denouncing the greed of the Anglican ministers and condemning the king's Privy Council for vetoing the Two Penny Act; since Britain's constitution, as well as Virginia's colonial charter, guaranteed the right to self-taxation, Henry contended that the Privy Council's decision to veto a colonial tax law was unconstitutional. Henry went a step further by blaming the king for not intervening to protect his subjects' rights; any king who refuses to protect the liberties of his subjects, according to Henry, "degenerates into a tyrant, and forfeits all rights to his subjects' obedience" (Middlekauff, 83).

At this, witnesses in the courtroom began to accuse Henry of treason, but since Henry's father was the presiding judge, he was not punished. Instead, Henry was allowed to finish his speech, which so moved the jury that they decided to award Maury the lowest possible sum of one penny. The affair greatly enhanced Henry's reputation, earning him 164 new clients in the following weeks, and eventually winning him election to the House of Burgesses in 1764. His diatribe against the king's tyranny made him one of the House's most radical members, a position that would enable him to take a leading role in the colonial protest of the Stamp Act in 1765. The Stamp Act was a policy passed by the British Parliament that directly taxed all paper documents in the colonies. Just as Henry had argued that the king had infringed on colonial rights by allowing the Two Penny Act to be vetoed, colonial leaders like Samuel Adams argued that Parliament was doing the same thing by taxing the colonies without their consent; the slogan 'no taxation without representation' became a battle cry throughout the colonies.

During his first legislative session in May 1765, Henry once again proved his radicalism by not only opposing the Stamp Act but denying that Parliament had any authority to tax the colonies at all. On 29 May, Henry spearheaded the passage of five resolves through the House of Burgesses, which essentially declared that only Virginia had the right to tax Virginians and that Parliament's attempts to do so were unconstitutional. The so-called Virginia Resolves were widely published in the colonies and Great Britain and thrust Virginia to the forefront of the colonial resistance, alongside Massachusetts. The resolves also cemented Henry's own reputation as a firebrand; in the speech in which he had proposed the resolves, Henry treasonously suggested that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) risked sharing the fate of Julius Caesar if he continued to trample on American liberties.

Fight for Independence

Although Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, it implemented another series of taxes that the Americans felt were equally oppressive. Worsening tensions led to instances of conflict, such as the Boston Massacre (1770), the Gaspee Affair (1772), and the Boston Tea Party (1773). It was in response to the Boston Tea Party that Parliament issued the so-called Intolerable Acts in 1774, which sought to make an example out of Massachusetts by closing Boston's port to commerce, installing a military governor, and replacing several public officials with royal appointees. The House of Burgesses was among the first to officially condemn the Intolerable Acts, leading Virginia's governor, Lord Dunmore, to dissolve the House; afterward, additional colonies announced their support for Massachusetts. In September 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to discuss a coordinated colonial response. Henry served as a delegate from Virginia at the Congress.

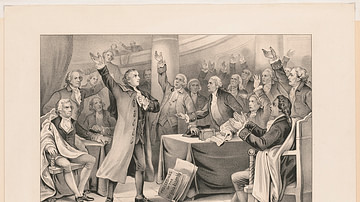

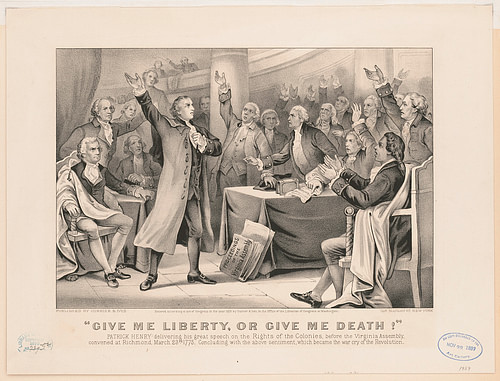

By March 1775, it seemed like war was inevitable; Massachusetts militias were already training for conflict with British soldiers, and Henry believed Virginia had to follow suit. On 23 March, he delivered a speech before the Second Virginia Convention (an assembly that met in place of the dissolved House of Burgesses) in which he argued in favor of raising a Virginian militia that was unbeholden to royal authorities. Henry contended that Great Britain had already provoked a conflict, first by issuing unjust laws, then by ignoring peaceful American remonstrances, and finally by sending soldiers to suppress colonial dissent. The only way to defend American liberties, Henry argued, was through war. In closing his speech, which was one of the most famous to come out of the American Revolution, Henry proclaimed:

Gentlemen may cry, 'Peace, Peace'– but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death! (Campbell, 130)

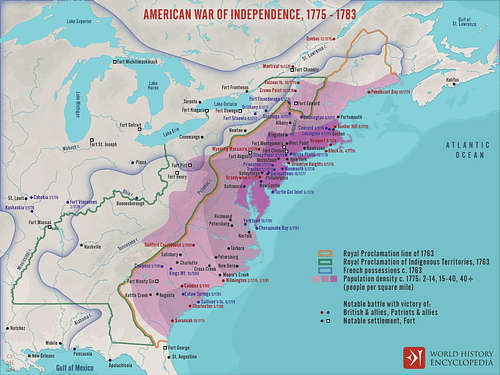

Henry's oration won over his fellow delegates, who authorized a committee to oversee the creation of a Virginian militia. For Henry, the decision came not a moment too soon. On 20 April 1775, Lord Dunmore ordered a detachment of British marines to seize the public gunpowder magazine at Williamsburg, to keep it out of the hands of Henry's militia. In response, Henry personally led a small group of his militia to Williamsburg, leading to a standoff with Dunmore's troops. The crisis was averted in early May when the governor agreed to pay £330 in compensation for the 'stolen' gunpowder. But although this so-called 'Gunpowder Incident' ended peacefully, news soon reached Virginia that blood had already been spilled in Massachusetts at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April). The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) had begun.

Politics

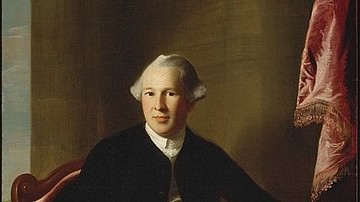

In May 1775, Henry once again went to Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress, which began to manage the colonial war effort. Simultaneously, Henry continued overseeing the organization of the Virginian militia and was even granted the rank of colonel when two of his militia regiments were incorporated into the Continental Army; however, after learning that this position would make him subordinate to several of his political rivals, Henry resigned his command. With the end of his brief military career, he returned to politics. He helped write Virginia's constitution as well as the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which served as an inspiration for the later constitutional Bill of Rights. He supported independence and, after the Continental Congress adopted the United States Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776, became the first governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

As governor, Henry was primarily concerned with military issues. He worked closely with General George Washington to provide men and supplies for the Continental Army and dispatched George Rogers Clark to defend the Ohio River frontier against the British. He served two one-year terms before leaving office in 1779, to be succeeded by Thomas Jefferson. He returned to Leatherwood Plantation, the 10,000-acre Henry County estate that he had purchased shortly after marrying his second wife, Dorothea Spotswood Henry, in 1777; Sarah Shelton Henry had died after an illness in early 1775. With Dorothea, Henry would have eleven children, in addition to the six he had had with Sarah. By this point, Henry also owned some 42 slaves, having been a slaveowner since the age of 18. Henry publicly denounced the institution of slavery, although he never proposed any legislation to combat it while in office, nor did he free his own slaves.

In 1780, Henry won election to the Virginia House of Delegates, where he was easily one of the most influential members. As the end of the Revolutionary War appeared on the horizon, American politicians began shifting their focus to what a post-war United States government would look like. Such discussions created fractures within the Virginia House of Delegates, where Henry often found himself opposed to James Madison. A primary point of contention between the two men was the issue of separation of church and state. While Henry supported religious freedom, he nevertheless believed that public taxes should help support religious institutions while Madison, and his ally Jefferson, believed in a complete separation between church and state. Henry was ultimately defeated on this issue in 1784 when Madison and Jefferson passed their Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.

Opposition to the Constitution & Later Life

In 1784, Henry was elected to the governorship of Virginia for a second time, becoming both its first and sixth governor. By this point, the Revolutionary War was over, and two factions had broken out: the Federalists, including Henry's rival Madison, wished to see a stronger federal government while the Anti-Federalists, including Henry, believed that a strong federal government would result in some states wielding undue influence over others. In 1785, Henry announced his support for the strengthening of the existing Articles of Confederation, after becoming increasingly concerned about rising Federalist support. In 1786, he left office and returned to the House of Delegates, where he continued to support the Anti-Federalist agenda.

In 1787, the Constitutional Convention met to revise the Articles of Confederation, which many Americans considered to be broken. Henry had been elected to the Convention but refused to attend after looking over a copy of the proposed Constitution that had been sent to him by George Washington. "I have to lament," Henry said, "that I cannot bring my mind to accord with the proposed constitution" (Encylopedia Virginia). Madison predicted that Henry would become the main obstacle to Virginia's ratification of the constitution, which came true in 1788 when Henry won election to the state's ratification convention. Henry became the convention's leading Anti-Federalist; utilizing his trademark eloquence and fiery oratory style, he declared that the constitution would destroy the powers of the states. He denounced the constitution as "extremely pernicious, impolitic, and dangerous" and warned that its adoption would be "a revolution as radical as that which separated us from Great Britain" (Patrick Henry's Red Hill). He ultimately lost the argument, and Virginia ratified the constitution by a vote of 89-79.

After his defeat, Henry retired from politics and returned to the practice of law. Despite his fierce anti-federalism, his attitude toward the constitution softened in the coming years, especially after the adoption of the Bill of Rights assuaged many of his concerns about a strong central government. Henry became receptive to the new Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton, especially once the Democratic-Republican Party of Madison and Jefferson showed support for the French Revolution (1789-1799); like many Federalists, Henry was disgusted by the radicalism and bloodshed of the French Revolution. Having shifted political allegiances, it seemed that Henry was poised to re-enter politics, although his failing health forced him to decline appointments as secretary of state and as a United States Supreme Court justice.

Henry finally re-entered politics in 1799, being persuaded to do so by former President Washington after an upsurge in Democratic-Republican influence. He was elected once again to the Virginia House of Delegates on 4 March 1799, this time representing Charlotte County (he had purchased a home, Red Hill, there in 1794). His last public speech was delivered at the Charlotte County courthouse on election day, in which he called for national unity. Before any legislative session could meet, Henry fell ill and returned to Red Hill, where he died of intussusception on 6 June 1799, at the age of 63. He owned 67 enslaved people at the time of his death, none of whom were freed in his will.

Henry's death was lamented throughout the United States, even by his political rivals. Today, he is best remembered for his passionate revolutionary orations, especially his Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death speech, which has been quoted by politicians and revolutionary movements many times in the centuries since it was first uttered. He is often celebrated as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States.