Turquoise was a highly-prized material in ancient Mesoamerica, perhaps the most valued of all materials for sacred and decorative art objects such as masks, jewellery, and the costumes of rulers and high priests. Turquoise was acquired through trade, the finest coming from the American southwest. The stone was also associated with deities like the fire god Xiuhtecuhtli, known as 'Turquoise Lord'.

Properties & Trade

Turquoise (copper aluminium phosphate) is a semi-precious stone, typically with an opaque appearance. The colour of turquoise found in Mesoamerica varies from a darker greenish-blue to lighter shades like sky blue and aquamarine (Persian turquoise, for example, is very rarely green in hue). The stone's green to blue colour variations reflect the varying levels of iron or copper in the stone. Pieces commonly include areas of dark veining caused by iron oxides.

Turquoise is a relatively soft stone making it easy to cut and carve; it can be polished to give a waxy lustre. Unfortunately, the colour of turquoise can deteriorate over time, and this accounts for the rather dull shades of some of the Mesoamerican artefacts made in that material which have survived to the present.

Turquoise was prized because of its rarity, as there were no sources of it in most of Mesoamerica, and it had to be imported through trade. Although turquoise dating to the Preclassic Period (2nd-1st millennium BCE) has been found, significant regional trade in the material only really started in the Early Postclassic Period (from 1000 CE). Most turquoise used in Mesoamerican cultures came from what is today New Mexico, specifically the Cerillos region, as indicated by chemical analysis of artefacts. Turquoise was available in northern Mexico but was inferior in quality to stone from New Mexico. Mesoamerican goods like exotic bird feathers were traded in exchange. Such was the importance of turquoise to regional trade, the routes from Mesoamerica to the American Southwest have been compared to the Silk Routes from China to Europe and so called the 'Turquoise Road'.

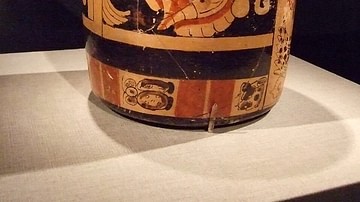

The first major Mesoamerican culture to use turquoise extensively was the Toltec civilization of central Mexico which flourished between the 10th and 12th centuries, but it was highly prized by others such as the Maya, Tarascans, and Aztecs (aka Mexica). Although largely reserved for the political, religious, and military elites, turquoise was gathered in large quantities, as shown by the excavations at Casas Grandes (aka Paquimé) led by Charles Di Peso, which discovered warehouses filled with the precious material. Similarly, finds of storehouses of turquoise at Alta Vista in northwest Mexico (where there are no local deposits) show that the scale of production was quite large. At Alta Vista, there is evidence the ore was collected and then worked into small finished tiles for distribution elsewhere in Mesoamerica. That turquoise was reserved for society's elite is shown in the graves of Alta Vista, where it was deposited along with other precious materials in rich tombs clearly indicating the occupant belonged to the higher echelons of the community. Maya sites like Chichen Itza also show that turquoise was imported. Aztec rulers included unworked turquoise in the list of goods they extracted as tribute from conquered tribes within their empire.

Common Uses

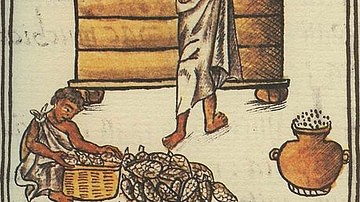

Craftworkers able to make art from materials like shell and turquoise were highly esteemed in Mesoamerican cultures. For example, artisans who worked turquoise were housed in a distinct part of the royal palace at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the totocalli or "bird house".

Turquoise was commonly used as an inlay material for jewellery such as diadems, necklaces, pendants, anklets, bracelets, belts, pectorals, earplugs, and studs (commonly worn in the lower lip by the nobility). It could be worn as beads on various parts of the body or as additions to more complex pieces of jewellery. As mosaic, turquoise was used to cover almost anything from knife handles to mirror frames. Typically, the backing material of mosaic work was wood, with the tiles (tesserae) glued on using pine resin. The natural colour variations of turquoise were often cleverly exploited by Mesoamerican artists when using small mosaic tiles to create effects of light and depth, accentuating the contours of the piece on which the tiles were applied. The Aztecs were great collectors of art pieces made by earlier Mesoamerican cultures, and they often embellished these older pieces by adding turquoise mosaic.

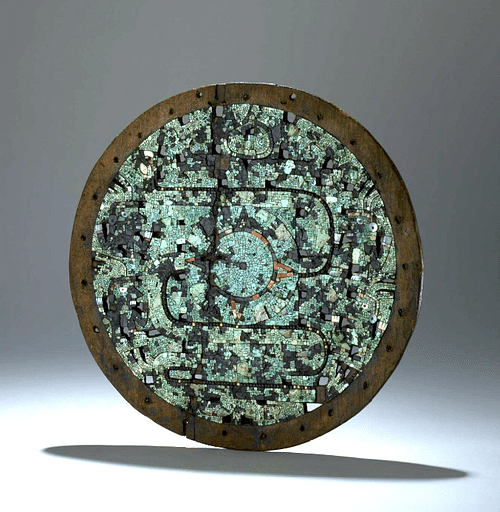

As a precious material, turquoise was used in votive offerings. A sacred cenote at Maya Chichen Itza, for example, contained many gold and turquoise discs thrown into it during religious ceremonies. Precious goods like those made with turquoise have also been excavated from the foundations of Mesoamerican temple pyramids, a fine example being the turquoise shield dedicated to the rain god Tlaloc which was buried beneath the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan.

Religious Associations

The esteem in which turquoise was held by ancient Mesoamericans is indicated in the stone's association with several important gods. Both the Toltecs and Aztecs worshipped Tonatiuh, the 5th and present sun in the Aztec view of the cosmos. His name translates as 'Turquoise Lord'. Indeed, the Aztecs thought that the Sun was made of turquoise.

Another major deity was the god of fire Xiuhtecuhtli, confusingly, also known as 'Turquoise Lord', perhaps because of the close link between fire and the Sun or even the blueness at the heart of an intense flame. The Nahuatl word for turquoise is xihuitl, a term also used for both fire and time itself or, perhaps more accurately, the solar year. Xiuhtecuhtli was associated with the xiuhtotl bird because it was a turquoise colour, and the god is often shown in art with such a bird perched on his forehead.

Depictions of gods wearing turquoise are seen in Mesoamerican wall paintings such as those created between the 11th and 12th centuries at Tulum on the east coast of the Yucatan peninsula in southern Mexico. Xiuhtecuhtli was envisaged in Aztec culture as wearing a pointed turquoise crown, breastplate, and mosaic shield. As Xiuhtecuhtli was also associated with warriors, they too wore items of turquoise, particularly pectorals in the form of stylised butterflies or dogs. Dead warriors were often cremated wearing paper-like imitations of turquoise jewellery.

Xiuhtecuhtli became associated with rulers during the Late Postclassic Period (13th-16th centuries), and so they, too, wore a pointed crown or diadem made of turquoise mosaic applied to a sheet of gold, the xiuhuitzolli. This crown was also a Nahuatl glyph and used to represent rulers, military leaders, judges, and the Aztec ruler Moctezuma I (r. 1440-1469). Aztec rulers also wore at their coronation ceremony the xiuhtlapilli tilmahtli, a blue cloak decorated with pieces of turquoise.

Effigies of gods were stood on the tops of temple pyramids, and these were often adorned with turquoise. The figure of the war god Huitzilopochtli, which stood on top of the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan, was so adorned. The fire serpents known as xiuhcoatl – Huitzilopochtli carries one as a weapon – were also thought to have skins covered in turquoise, and so these creatures are often represented as such in Mesoamerican art.

Mesoamerican priests often wore turquoise masks during important ceremonies. The Aztec New Fire Ceremony, also known as the Binding of the Years Ceremony or Toxhiuhmolpilia, was a ritual held only once every 52 years, the completion of a full cycle of the Aztec solar year (xiuhmopilli). The purpose of the ritual was none other than to renew the sun and ensure another 52-year cycle. During the ceremony, a high priest dressed as Xiuhtecuhtli and wore a turquoise mask as he sacrificed the heart of a living victim and attempted to begin a sacred fire in the now-empty chest cavity. If the fire did not light, the sun would not be renewed, and there would be no new 52-year cycle; in short, this would be the end of the Aztec world. The association with Xiuhtecuhtli and time explains why the symbol of turquoise was a circle with an hourglass in the centre. An alternative symbol for the semi-precious stone in the Late Postclassic Period was a quincunx (like the five on a dice), which was also how the Aztecs viewed their universe.

Turquoise Masterpieces

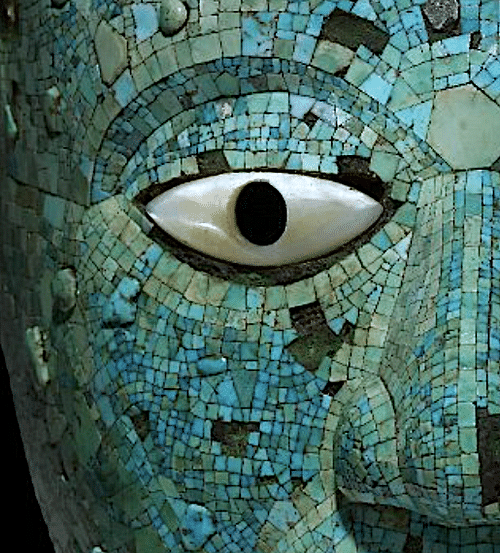

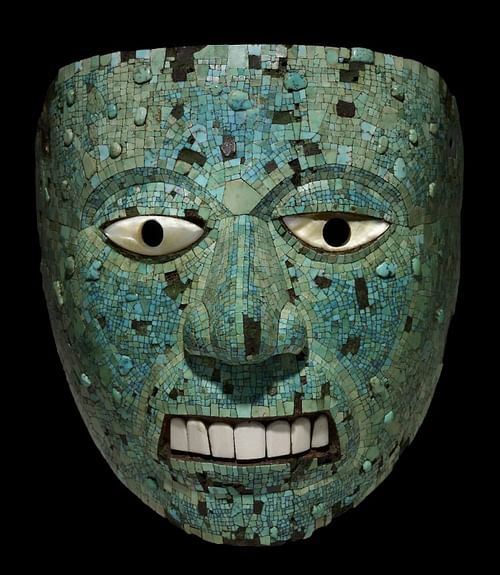

One of the most striking of all art pieces from Mesoamerica is a turquoise mosaic mask representing the fire god Xiuhtecuhtli which dates to 1400-1521 CE. The mask is of cedar wood with mother-of-pearl eyes, conch shell teeth, and it once had gold leaf on the eyelids. The outer surface is made of hundreds of turquoise tiles, with those around the eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth cut with particular precision. The choice of colour shades has been carefully considered, with lighter, bluer shades used where the light would naturally catch a face such as the nose, cheeks, and forehead.

A peculiar feature of the mask is the deliberate use of raised tiles at various points, almost like warts. These 'warts' have led some scholars to speculate that the mask may represent the sun god Tonatiuh, that deity having once been an old and wart-covered god who sacrificed himself by jumping into a fire, from which action Tonatiuh was born. In contrast, other scholars point out that the slightly darker shades of the tesserae on the cheeks and bridge of the nose create a stylised butterfly, as do those on the forehead, a creature closely associated with Xiuhtecuhtli and a symbol of change and renewal.

The mask was meant to be either worn by a god impersonator in religious ceremonies or worn by an effigy of the god, as indicated by the small hole on either side of the piece through which a cord would have passed. The mask was almost certainly part of the treasure brought back from Mesoamerica by the conquistador Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) and presented to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556). The mask is on permanent display in the British Museum, London.

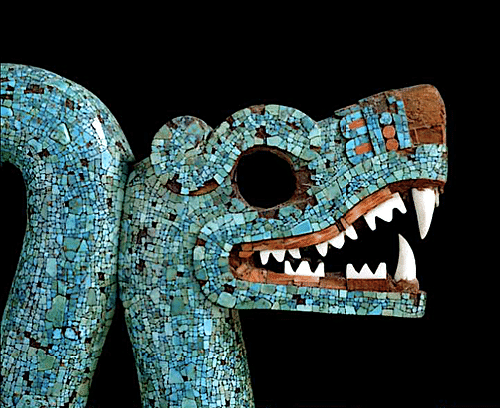

Double-headed Snake Pectoral

Another masterpiece in turquoise, and also now housed in the British Museum, is a striking double-headed snake pectoral. Contemporary with the mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, this piece is again of carved cedarwood which has been completely covered in small squares of turquoise. The two red mouths are of red thorny oyster shell, and the white teeth are conch shell. The eyes would once have been inlaid with a material like pyrite or obsidian, as indicated by remaining traces of beeswax.

This, too, was likely once part of a ceremonial costume probably in connection with the feathered-snake god Quetzalcoatl. The snake was a powerful and frequently-used image in Mesoamerican art as it represented regeneration (since the reptile regularly sheds its skin). The double-headed snake or maquizcoatl was considered a bad omen, but the name is also associated with Huitzilopochtli, and so this piece may have been worn across the chest of a high priest linked with that god. The work measures 17 inches or 43.3 centimetres across.

Tezcatlipoca Skull

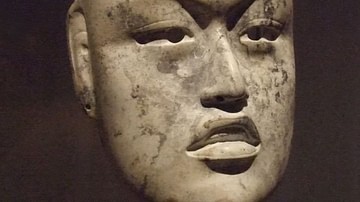

A third masterpiece of turquoise that has found its way into the British Museum is a human skull (male, aged around 30) covered in mosaic to represent the Toltec and Aztec god Tezcatlipoca who was closely associated with creation, warfare, and change through conflict. It may have been worn as a back ornament, although its interior lining and straps of deerskin may suggest otherwise. The god was frequently depicted in art with a black stripe across his face, and this is here represented by tiles of lignite. The eyes are rendered in polished pyrite with white conch shell, while the nose cavity is covered with red thorny oyster shell. Once again, the turquoise tiles have been expertly shaped to perfectly cover the contours of the skull behind them.