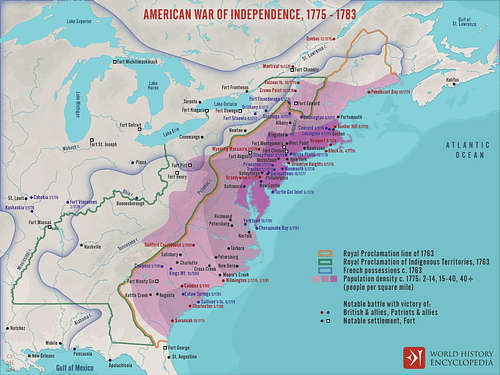

The New York and New Jersey Campaign (3 July 1776 to 3 January 1777) was a pivotal campaign waged during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) for control of New York City, the Hudson River, and the resource-rich state of New Jersey. Although the British occupied Manhattan, they failed to seize New Jersey or destroy the American Continental Army.

Since the outbreak of the war, both the British ministry and the Second Continental Congress saw New York as the key to victory or defeat; if the British seized Manhattan, they could sail an army up the Hudson River and into the American interior. In April 1776, General George Washington began preparing for the defense of New York City but was defeated by British General William Howe four months later at the Battle of Long Island (27 August). The Continental Army avoided destruction by successfully withdrawing to Manhattan, but the subsequent British landing at Kip's Bay (15 September) forced it to evacuate New York City as well. Although the Americans won a small victory at the Battle of Harlem Heights (16 September), they were soon forced out of Manhattan and were defeated at White Plains (28 October) and Fort Washington (16 November).

With the British now in complete control of Manhattan, Washington retreated into New Jersey, where he was pursued by Lord Charles Cornwallis. The British chased the Continental Army through New Jersey and into Pennsylvania, where it was in critical condition; plagued by smallpox, the Continental soldiers lacked shoes or coats and were soon deserting in droves. Realizing that he had to secure a victory soon, Washington crossed the Delaware River on Christmas Day and won a surprise victory over a Hessian garrison at the Battle of Trenton (26 December). He followed this up with another victory at Princeton (3 January), which forced the British out of New Jersey. The campaign ended, therefore, with the British in control of Manhattan and the port of New York but with the Americans maintaining control of New Jersey. Most significantly, the Continental Army survived to carry on the war.

Preliminary Movements

From the moment that Congress had named him commander of the newly formed Continental Army in the summer of 1775, George Washington had considered New York City and the valuable waterways it controlled as the key to an American victory. Confined entirely to the upper part of Manhattan Island, New York was the second largest city in the Thirteen Colonies, behind only Philadelphia, with a peacetime population of 20,000. Its port made it a bustling center of commerce and shipbuilding, while its tree-lined streets and grand brick houses lent it an elegance seldom seen in other colonial cities. As important as the city was itself, its strategic value was increased by the vast system of waterways it controlled; by way of the Hudson River and its tributary, the Mohawk, a route of navigable waters stretched nearly unbroken from New York Harbor to Canada. Therefore, if the British seized Manhattan, they could sail an army up the Hudson and deep into the American interior. It was feared that the loss of the Hudson would sever communication and hinder military cooperation between the northern and southern colonies.

In February 1776, Washington dispatched his second-in-command, General Charles Lee, to Manhattan to begin assessing the city's defenses. By the time Washington arrived on 13 April, Lee had become convinced that New York could not be held without naval superiority, a major problem since the Americans did not yet possess a navy. Washington had been told by John Adams that "no effort to secure [the Hudson] ought to be omitted" and was adamant about not giving the city up without a fight (Daughan, 5). Lee therefore provided Washington with a list of key locations that should be fortified, with a special focus placed on Brooklyn Heights on Long Island; Lee believed that the British could not hold Manhattan without first taking Long Island and could not take Long Island without capturing Brooklyn Heights.

Washington agreed and ferried men over to Long Island. The Americans spent the next two months fortifying the heights, constructing four sturdy fortresses connected by a series of trenches. Hoping to deny the British access to the East River, the Americans put cannons on Governors Island, just off Manhattan, and built a fort on Red Hook, a small stretch of land that extended out into the East River from Brooklyn. At the northernmost end of Manhattan Island, the Americans constructed Fort Washington to guard the eastern entrance to the Hudson River; on the opposite side of the river, they built Fort Lee atop the New Jersey Palisades, hoping that the crossfire from the two forts would prevent the British from sailing up the Hudson. In the city, Washington's men tore up the streets to make trenches and barricades. Every day, the Continental soldiers prepared for a British landing; they slept with their muskets loaded, practiced running from their camps to the fortifications, and fired two rounds to familiarize themselves with their weapons.

On 29 June, the dreaded day arrived as a British frigate, HMS Greyhound, sailed into New York Harbor and anchored off Staten Island, carrying the commander of the British forces in North America, General William Howe. Over the next several weeks, the Greyhound was joined by over 400 British vessels, which began unloading British regular soldiers and their German auxiliary troops, commonly known as Hessians, onto Staten Island. By early August, General Howe's army numbered 32,000 men, making it the largest expeditionary force Great Britain had ever sent to any part of the world. Just as Washington and the Continental Congress had feared, Howe's plan was to seize Manhattan and the valuable port of New York before pushing north to secure the Hudson River; the British ministry hoped to march a secondary army down from Canada, which could link up with Howe and isolate the New England colonies, still considered to be the heart of the American rebellion.

The overwhelmingly Loyalist population of Staten Island ensured that the British and Hessian troops were comfortable, providing them with food and shelter, but across the harbor, on Manhattan, the Patriots had begun to hold sway. On 9 July, after Washington had read the United States Declaration of Independence aloud to his men, a crowd of Sons of Liberty tore down the gilded lead statue of King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) on Bowling Green and melted it down for bullets.

Fighting for Long Island

In mid-July, the British were joined by Admiral Lord Richard Howe, the general's elder brother, who had been granted the authority to negotiate with the Americans. Unlike the king's ministry, which was intent on securing a complete victory so that the king could dictate terms, the Howe brothers believed reconciliation to be the best policy; they sent a messenger to Washington, offering to grant pardons if the Continentals agreed to lay down their weapons and renounce the United States' independence. Washington flatly refused, telling the messenger that "those who have committed no fault want no pardon. We are only defending what we deem our indisputable rights" (McCullough, 146). Their overtures for peace brushed aside, the Howes landed 15,000 British and Hessian troops at Long Island's Gravesend Bay on 22 August. Not only did the troops land unopposed, but they were also greeted by large crowds of jubilant Loyalists from Brooklyn and the island's other hamlets.

The landing took Washington off-guard, and it was a whole day before he responded. He moved 4,000 men off Brooklyn Heights, having them form a preliminary line of defense on the Heights of Guan, a densely wooded ridge that sat just in front of Brooklyn. The Guan Heights had three major passes through them, which were each defended by a body of American troops. However, there was a fourth, lesser-known path known as the Jamaica Pass that extended through the woods on the far-left side of the heights. The Americans had left this pass unguarded except for five militia officers stationed there. On the night of 26 August, three Brooklyn Loyalists guided a column of British troops under Sir Henry Clinton up the Jamaica Pass, where they waited until dawn. Then, while the Continental troops on the Guan Heights were pinned down by a series of British diversionary frontal assaults, Clinton sprung the trap and flanked the Americans. Finding themselves surrounded, the Americans panicked and were driven from the heights.

The Battle of Long Island was a catastrophic defeat for the Americans, who lost nearly 1,000 men killed or wounded, with another 1,000 captured; most of these prisoners would die of disease or malnutrition aboard the infamous British prison ships that would soon be anchored off Brooklyn. The British and Hessians, by contrast, had lost only 64 killed and around 300 wounded. General Howe had the opportunity to storm the remaining American fortifications atop Brooklyn Heights, but he hesitated. Then, after a whole day of doing nothing, he finally ordered his men to start digging breastworks at the foot of the heights, in the preparation of a siege.

Historians have long speculated as to why Howe did not storm the heights; perhaps he did not want to risk the lives of his men in an unnecessary frontal assault, or perhaps he did not want to completely destroy the Continental Army. In any case, his delay allowed the Continentals to slip through his fingers; during a storm on the night of 29-30 August, the Continental Army slipped off Brooklyn Heights and withdrew to Manhattan. Though Long Island was now under British control, the Continental Army was still intact.

The British Occupy Manhattan

In the first few days of September, Washington's battered army licked its wounds in New York City while the Howe brothers once again sued for peace. On 11 September, they met with a Congressional delegation on Staten Island that included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge; the Americans were unwilling to renounce their independence, and the peace talks quickly broke down. On 15 September, five British warships sailed up the East River and opened fire on Kip's Bay on the shore of Manhattan, where 500 Connecticut militiamen were hiding in their trenches. After hours of continual bombardment, the British cannons went silent as 4,000 British and Hessian troops rowed toward the shore in flatboats. The militiamen panicked and began to flee; in one of the only instances in which the usually stoic Washington lost his temper, the general flung his hat to the ground and began lashing the runaway troops with his riding crop. He was so blinded by rage that he had to be led away by his officers, lest he be captured by the approaching British troops.

That same day, Washington evacuated New York City, withdrawing his army further down Manhattan to Harlem Heights (modern-day Morningside Heights). On 16 September, a British assault was repulsed at the Battle of Harlem Heights, and the two armies settled into their positions, with neither budging for the next month. Washington was forced to watch as Howe's red-coated soldiers filtered into New York City; he had wanted to burn it to the ground rather than see it fall into British hands, but Congress had ordered him not to. However, on 21 September, less than a week after the British occupied it, New York City caught fire, and 10-25 % of its buildings were destroyed. The British blamed the Americans, with some British soldiers having claimed to have caught Patriot incendiaries in the act. Publicly, Washington denied responsibility, although he clearly considered the fire to be good news. He later wrote to his cousin that "Providence, or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves" (McCullough, 223).

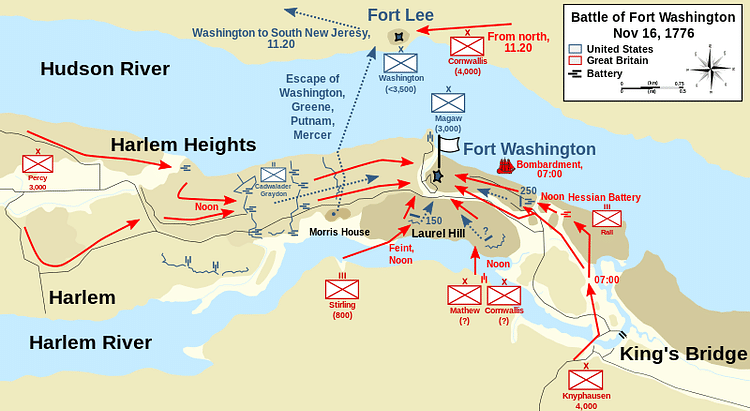

On 18 October, General Howe landed 4,000 troops at Pelham in the Bronx, intending to outflank Washington's position. Realizing that his army would be destroyed if the British were able to surround it, Washington pulled off Harlem Heights and decided to evacuate Manhattan altogether. But before he did, he was persuaded by his most trusted subordinate, General Nathanael Greene, to leave a garrison in Fort Washington, at the northernmost point of Manhattan beside the Hudson River; the fort could allow the Americans to keep a toehold on Manhattan and could pin down British troops who would otherwise be used to invade New York or New Jersey. Washington agreed and left 3,000 men in the fort under Colonel Robert Magaw before leading the rest of his army out of Manhattan and into New York's Westchester County.

Howe initially pursued, defeating Washington in the minor Battle of White Plains (28 October). However, rather than pursuing the Continental Army as it retreated, Howe swiveled back south to deal with Fort Washington, the last remaining obstacle to full British control of Manhattan. On 15 November, he sent a messenger to the fort under a flag of truce with a message: surrender or the entire garrison would be put to the sword. Colonel Magaw refused, telling the messenger that since he was "activated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought in, I am determined to defend this post to the last" (Middlekauff, 359). The next day, Howe launched a three-pronged assault on Fort Washington, driving the defenders back from their outer defenses within the first hour of fighting. Before long, Magaw had changed his tune and surrendered the fort and its garrison of 2,800 men; only 800 of these prisoners would survive the abysmal conditions of the British prison ships. The Battle of Fort Washington was one of the worst defeats suffered by the Continental Army and secured British control of Manhattan, which they would occupy for the rest of the war.

Retreat & Counterattack

Meanwhile, General Washington had divided his army; he led 3,500 troops across the Hudson and into New Jersey, leaving 5,500 troops under General Charles Lee behind in North Castle, New York, to prevent the British from moving north toward Albany. On 20 November, British General Lord Charles Cornwallis sailed across the Hudson and captured Fort Lee in New Jersey, which the Americans had abandoned only hours before. Hoping to capture Washington's army in the same way that "a hunter bags a fox" (McCullough, 253), Cornwallis led a column of 10,000 troops in pursuit of the Continental Army, which was rapidly disintegrating. Ravaged by smallpox and forced to march through rain and mud without shoes or coats, the American soldiers were deserting in droves. If nothing was done, the army was likely to have vanished by the new year.

Washington arrived at Newark on 22 November, resting for five days before pushing south toward New Brunswick, with Cornwallis in hot pursuit. He entreated General Lee to join him, but Lee, who resented what he saw as Washington's incompetent command, was slow to move. In early December, Lee finally entered New Jersey but unwisely decided to spend the night at a tavern and was captured. General John Sullivan took command of his army and marched to join Washington, who, by this time, had exited New Jersey, having crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. At this point, Cornwallis stopped pursuing, and the British entered winter quarters. It appeared that the American rebellion was on the point of collapsing; Washington's disease-ridden army was close to destruction, and the Continental Congress had evacuated its capital of Philadelphia for the safer location of Baltimore, Maryland. Moreover, the resource-rich New Jersey had fallen into British hands; hundreds of the state's residents were flocking daily to British camps to declare their loyalty to the king. It seemed as if the United States, not even half a year old, would soon be destroyed.

Washington knew he had to act now. With the enlistments of most of his men set to expire in the new year, even defeat would be preferable to doing nothing. His only hope was to catch the enemy while they were in winter quarters; traditional European armies did not typically fight in the winter unless absolutely necessary, giving Washington the advantage of surprise. On the night of 25 December, he crossed over the icy Delaware River and re-entered New Jersey with 2,500 men; the next morning, he attacked the Hessian garrison at Trenton. Reeling from the previous night's Christmas celebrations (though they were not still drunk, as was later alleged), the Hessians were taken off-guard and defeated. Washington took 900 Hessians prisoner without losing a single American life.

The Battle of Trenton greatly raised American morale and galvanized support for the American Revolution; many of Washington's men re-enlisted, while other Americans were inspired to enlist for the first time. The battle also lured Cornwallis out of his winter quarters. On 2 January 1777, he attacked Washington's position at the Battle of Assunpink Creek, but his assaults were repulsed. During the night, Washington once again used stealth to march around Cornwallis' army and strike the British rearguard at Princeton. At the Battle of Princeton (3 January), Washington surprised and defeated the British rearguard, winning another small yet significant victory.

The defeats convinced General Howe to withdraw most of the British army from New Jersey, as Washington took up winter quarters in Morristown. Aside from minor, yet bloody, skirmishes between American and British foraging parties, the fighting of the New York and New Jersey Campaign was over; having been on the point of collapse only weeks before, the Continental Army had saved New Jersey from falling into British control and, most importantly, lived to fight another day.