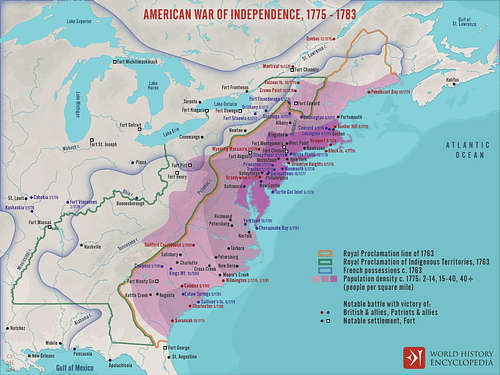

The Battle of Kings Mountain (7 October 1780) was a significant battle of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), fought in the backcountry of South Carolina between large parties of Patriot and Loyalist militias. The battle exemplified how the American Revolution could often take on the characteristics of civil war, as most participants on either side were Americans.

The Subjugation of the South

On 12 May 1780, the city of Charleston, South Carolina, fell to the British army after a grueling six-week siege. It was one of the greatest British triumphs of the war so far. Charleston was the largest and most important city in the American South, and its capture provided the British with an excellent base from which to invade the rest of the region. Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army, did not believe that the subjugation of the South would be a difficult feat. It had long been rumored that the South was replete with Tories (or Loyalists) who felt oppressed by their new revolutionary governments and yearned for the return of royal authority. Clinton believed that the mere presence of British soldiers in the region would trigger a massive revolt of thousands of southern Tories, who would help the soldiers reconquer the South in the name of the king.

Once Charleston fell, Clinton immediately turned his attention to prodding South Carolina's Loyalist population into action. To achieve this, he appointed Major Patrick Ferguson as Inspector of Militia for the Southern Provinces, tasking him with the recruitment and organization of Tory militias. The Scottish-born Major Ferguson seemed to be an excellent candidate for such a task. A career soldier, Ferguson had entered the British army in his teens and had fought in the European theater of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). He had patented a new kind of breechloading rifle that allowed for a higher rate of fire than the standard flintlock musket, even in wet weather; his British comrades, however, preferred the familiarity of their 'Brown Bess' muskets, and only 200 of Ferguson's Rifles were ever manufactured. Major Ferguson also had a sense of military honor. He claimed that during the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777), he had had an opportunity to shoot an American officer that he believed to be George Washington but had declined to do so, believing that it was dishonorable to target officers.

Ferguson was still only a major after his decades of military experience and was eager to prove himself worthy of his new command. Shortly after his appointment as Inspector of Militia on 22 May 1780, he rode to Tryon County, which was heavily populated by Loyalists, and spent the following months recruiting Tory militias. By August, he had raised around 4,000 Tory militiamen from across the South Carolina backcountry; while these numbers were impressive, they fell far short of the total number of Tories that Clinton had expected would rally to the British cause. But Ferguson made good use of what he had. During the summer of 1780, his Tories performed well in a series of skirmishes with Patriot militia that took place in the territory between the fortress of Ninety-Six and the North Carolina border. By the end of August, Ferguson had successfully driven most Patriot partisans from the northwestern part of South Carolina.

Ferguson's success against the Patriot militias was soon bolstered by an even more significant British victory. On 16 August 1780, the main British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis decisively defeated an American army at the Battle of Camden. The battle not only secured British control of South Carolina but also cleared a path for Cornwallis to launch an invasion of North Carolina (Cornwallis had taken over command from Clinton, who had returned to New York to keep an eye on Washington's army in the north). In early September, as Cornwallis prepared to march his army to Charlotte, North Carolina, he ordered Ferguson to enter the state first and begin recruiting and organizing militias of North Carolina Tories. Ferguson was then expected to defend the left flank of Cornwallis' army as it commenced its invasion. The Scottish major quickly rode into North Carolina to fulfill this new mission, eager to help play a role in Britain's subjugation of the South.

Over the Mountains

Of course, Ferguson's Tories were not the only Americans enlisting in militias. Even before the Siege of Charleston, Patriot militias had begun to pop up in the South Carolina backcountry, armed with tomahawks and hunting rifles and clothed not in uniforms but only in whatever homespun clothes they happened to have on. After the crushing defeats of the regular Continental Army at Charleston and Camden, these militias became the only obstacle between the British and the domination of South Carolina. Led by men such as Thomas Sumter, Andrew Pickens, and Francis Marion, these militias proved to be a thorn in the British side, striking at small detachments of British and Tories before melting back into the woodlands and swamps. As has been noted, Ferguson spent the summer of 1780 clearing these pesky militias out of the northeastern part of the state. Most of the skirmishes were small affairs, resulting in only a handful of casualties. However, the psychological impact was as devastating as any pitched battle, as militiamen often found themselves fighting against their neighbors and relatives.

Having been chased out of South Carolina by Ferguson, several small bands of Patriot militia sought refuge on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains. They found sanctuary in one another's company and soon coalesced into a makeshift militia army, under the joint command of colonels Isaac Shelby, William Campbell, John Sevier, and Joseph McDowell. The militiamen themselves were mostly rugged frontiersmen, while their leaders were propertied gentlemen; all of them, however, longed to return to South Carolina and hated Ferguson and the Tories for forcing them out. Ferguson, meanwhile, appreciated the threat posed by this large assembly of Patriots. On 10 September, he reached Gilbert Town, North Carolina, and established a base there. Many residents came out to swear allegiance to the king and enlist in Tory militias. Emboldened by this success, Ferguson sent a paroled prisoner to the Patriot camp across the Appalachians with a message. If they did not immediately disband and swear oaths of fealty, Ferguson threatened to "march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword" (Boatner, 576).

The militia, now known as the 'Overmountain Men', was spurred to action. They had been joined by the frontiersmen of the Appalachian Mountains, as well as from the territories that would become Tennessee and Kentucky, who had been provoked by Ferguson's threat to burn their homes. It was decided that any frontiersman who wished to fight the Tories should muster at Sycamore Shoals (modern Elizabethton, Tennessee) on 25 September 1780. When the day arrived, around 1,100 Overmountain Men arrived for duty. The next day, this ragged army set off over the frigid mountains, arriving in North Carolina on 30 September. They paused for a day of rest at Quaker's Meadow where they were joined by an additional 350 North Carolina militia led by Colonel Benjamin Cleveland. Before setting off for Ferguson's camp at Gilbert Town, the five colonels in charge of the expedition (Shelby, Campbell, Sevier, McDowell, and Cleveland) elected William Campbell as their commander.

Ferguson Retreats

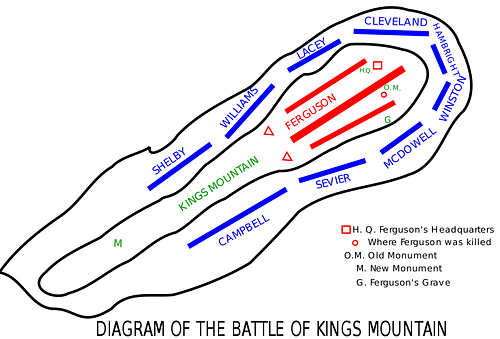

Meanwhile, two Patriot deserters informed Ferguson that a large rebel force was headed his way. Ferguson decided to retreat to Lord Cornwallis' position at Charlotte and left Gilbert Town on 27 September. By 1 October, the Scottish major had reached Broad River, where he sent out a proclamation to the surrounding towns, calling on the local Tories to join him. At this point, Ferguson seems to have changed his mind about seeking refuge with Cornwallis' army. Although Charlotte was only a day's march away, Ferguson seems to have been tempted by the prospect of defeating the Overmountain Men by himself. After sending a dispatch to Charlotte to request reinforcements, Ferguson marched his men up Kings Mountain, the high point of a 16-mile (26 km) mountain range on the border between North and South Carolina. The mountain was an excellent defensive position. Ferguson decided to make his stand on a ridge that was shaped like a human footprint, with the 'toe' pointing to the northeast. This spot was defended by steep slopes that were densely covered in pine trees and boulders. Ferguson was so confident in the mountain's natural defenses that he did not bother adding to them.

The Overmountain Men reached Gilbert Town on 4 October. After learning that Ferguson had gone, they pushed south and reached the meadow of Cowpens, South Carolina, on 6 October (this would be the site of the significant Battle of Cowpens three months later). It was here that the Overmountain Men learned that Ferguson was encamped on Kings Mountain. This was an excellent opportunity to trap their hated enemy, and the Overmountain Men marched nonstop throughout the night and into the next morning, their mood dampened by an incessant drizzle. By the early afternoon of 7 October, the Patriots had approached the mountaintop where Ferguson's men were positioned. Colonel Campbell told his men to "shout like Hell and fight like devils" before dividing them into eight groups of about 100 men each (Boatner, 581). The Patriots had about 900 men in total, while the Tories had around 1,100. Except for Ferguson himself, everyone on the battlefield was an American, making the forthcoming battle the largest 'all-American' fight of the Revolutionary War.

The Battle

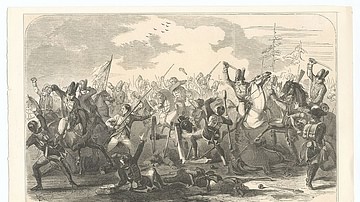

The Patriots silently crept up the mountain toward the Tory position; each of the eight detachments approached the mountaintop from a different side so that Ferguson's men were completely surrounded. The first indication that the Tories had that something was wrong was when the Patriots emerged from the tree line, firing their muskets and screaming like demons. Ferguson had been so confident in the strength of his position that he had failed to post enough guards, allowing the Patriots to sneak up on him in such a manner. As the startled Tories scrambled to grab their muskets and fire at the approaching Patriots, they realized another mistake that stemmed from Ferguson's overconfidence: the dense pine trees and boulders that dotted the slopes did nothing to protect the Tories, as Ferguson had intended, but rather gave the Patriots cover to shelter behind as they made their way up the mountainside.

Ferguson quickly realized that musket volleys would be futile and ordered his men to fix bayonets, hoping that a frantic bayonet charge would be enough to sweep the Patriots off the mountain. The Tories ran headlong into Campbell's frontiersmen, and the fight devolved into bloody hand-to-hand fighting; men were skewered by bayonets, while others were shot at point-blank range. But the rugged Overmountain frontiersmen were not so easily shaken, and the Tories were soon pushed back up to the mountain's crest. The combined forces of militia colonels Campbell, Shelby, and Sevier (about 300 men) then began to push onto the crest themselves, slowly driving the Tories back toward the Patriot forces that were approaching from the other side. The Tories were trapped and, if they did nothing soon, would be slaughtered.

The energetic Ferguson seemed to be everywhere during the fighting. He galloped back and forth atop his white horse, blowing a silver whistle to keep his men orientated. Whenever he noticed that his men were on the point of breaking, he would ride over and harangue them, at times using his saber to cut down white flags that his men were attempting to raise. Before long, the Tories had been pushed back to their camp and were facing Patriots on every side; the only hope now was for them to fight their way out of the encirclement and escape down the mountain. Ferguson attempted to lead such a counterattack and charged forward, only to be shot from his saddle; a Patriot named Robert Young later took credit for shooting Ferguson with his rifle that he had named 'Sweet Lips'. The wounded Ferguson was then dragged behind Patriot lines, where he was approached by a Patriot officer who demanded his surrender. Ferguson did not speak but fired his pistol, shooting the officer dead; the Patriots responded by firing six times into the wounded Scottish major, killing him.

With the death of Ferguson, the Tories realized that all hope was lost. Captain Abraham de Peyster, who took command of the Tory force, sent a man out with a white flag, in an attempt to surrender. For several minutes, the Overmountain Men ignored this and kept on killing, slaughtering the Tories even after they had thrown down their weapons; this was done in revenge for the Battle of Waxhaws (29 May 1780) when the British and Tories had slaughtered surrendering Patriots in a similar way. It was only with great difficulty that Patriot colonels Campbell and Sevier were able to rush forward and gain control of their men, stopping the massacre before it went too far. De Peyster sent out another emissary with a white flag (the first had been killed), and the Patriots accepted his surrender. 157 Tories had been killed during the battle, 163 were badly wounded, and the other 698 were taken prisoner; the Patriots, by contrast, lost 28 killed and 64 wounded. The fighting had lasted only 65 minutes.

Aftermath & Significance

The Patriots were forced to evacuate Kings Mountain as quickly as possible since Cornwallis' main British army was still close by. Because of this hastiness, they abandoned the most severely wounded Tories on the battlefield, since they were unable to carry them off. On 8 October, the Overmountain Men returned to Gilbert Town, North Carolina, where they held makeshift courts-martial for their prisoners. 36 Tories were convicted of certain crimes and nine were hanged before Colonel Isaac Shelby put an end to the extrajudicial proceedings. The remaining Tory prisoners were entrusted to Colonel Cleveland's command and were marched toward Hillsboro, North Carolina; however, Cleveland did not have adequate resources to watch the prisoners, and all but 130 escaped into the woods during the march to Hillsboro. Having accomplished its goal of defeating Ferguson, the great Patriot militia army broke apart. Most of the men returned to their homes, while others resumed taking part in guerilla operations against the British.

The Battle of Kings Mountain, though relatively obscure today, was arguably one of the most significant engagements of the entire Revolution. It was a much-needed victory, coming after a series of devastating Patriot defeats at Savannah, Charleston, Camden, and Waxhaws. The Tories of South Carolina had been completely broken militarily and ceased to pose a serious threat. This meant that Cornwallis was forced to return to South Carolina, as he no longer could rely on Ferguson's Tories to keep the Patriot militias at bay. Cornwallis would not return to North Carolina until the following year. For these reasons, Kings Mountain could rightfully be considered the turning point of the southern theater of the war. Combined with the subsequent Patriot victory at Cowpens in January 1781, the battle rescued the South from falling completely to the British, and it helped pave the way for Washington's final victory at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781).