The history of green tea in Japan goes back to the 8th century when it was a popular stimulant for meditating monks. In this article, we examine tea's origins and cultivation, how it became an integral part of Japanese culture, the symbolism of the Japanese Tea Ceremony, and how one should drink tea according to traditional Japanese principles.

As the Japanese writer Kakuzo Okakura (1862-1913) noted in his famous work The Book of Tea: "Tea with us became more than an idealisation of the form of drinking; it is a religion of the art of life" (28).

Buddhist Origins

In Chinese and Japanese traditions, the discovery of tea (cha) is credited to the 5-6th century Indian sage Daruma (aka Bodhidharma), the founder of Chan Buddhism, a precursor of Zen Buddhism. Daruma, spread the word of his new doctrine and founded the Shaolin temple in eastern China (Shorinji to the Japanese). There he meditated while sat facing a wall for nine long years. At the end of that period, his legs had withered away, and, just on the verge of reaching enlightenment, he fell asleep. Enraged at missing this last step, he ripped off his eyelids and threw them to the ground. From these, a bush grew, the tea plant.

The tea drink is made by adding hot water to the young leaves, leaf tips, and leaf buds of the evergreen shrub Camellia sinensis, which is native to the hills of southwest China and/or northeast India. In this early period, it was prepared by boiling bricks of fermented tea, and salt was often added.

Tea became popular with Zen Buddhist monks as it was thought to aid meditation and ward off sleep. The caffeine content of tea, while less than in coffee (14-61 mg versus 95-200 mg per 8 oz serving), makes the drink a mild stimulant. Tea was thought to have medicinal qualities, perhaps even to help one's longevity. Tests have shown that tea's antioxidant tannins can strengthen the immune system. For some, tea was considered a cure for a hangover, a remedy for weakening eyesight, and (applied as a paste), even a cure for rheumatism.

Tea was introduced to Japan in the 8th century by visiting monks, traders, and diplomats. In addition, Japanese monks visited China and brought back such cultural practices as tea drinking. One such monk was Saichō (767-822), founder of Tendai Buddhism who, according to tradition, brought tea seeds to Japan around 805 and planted them in Yeisan. The earliest mention of tea in Japanese literature comes in the Nihon Koki, written c. 840. Here Emperor Saga (r. 809-823) is described as visiting Bonshaku temple and drinking a bowl of tea served by the monk Eichū (743-816). Impressed with the beverage, Saga had tea plants cultivated in several areas in western Japan.

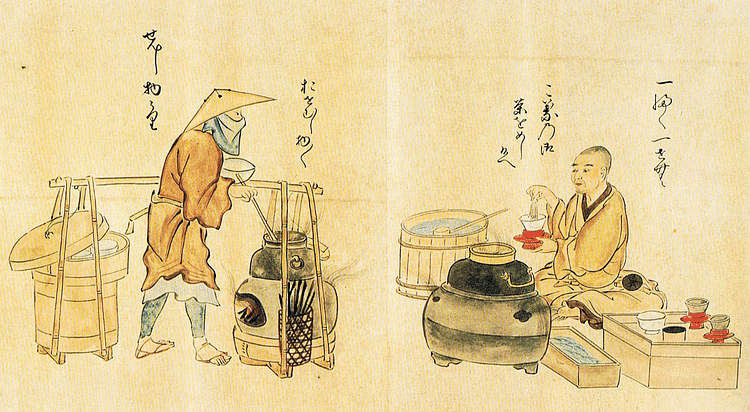

Tea consumption really took off in Japan from around 1190 when it was endorsed by the famous monk Eisai (1141-1215 CE), who established Rinzai Zen Buddhism in Japan. In 1214, Eisai even wrote a book extolling the virtues of tea, suggestively titled Drink Tea and Prolong Life (Kissa yojoki). Ordinary people could by now buy tea from street vendors. The first vendor mentioned in literature appears in a work dated to 1403. Tea vendors typically sold tea at street markets, by the sides of roads, and outside temples. Vendors would tout for business by crying out, ippuku issen!, meaning "a bowl for a coin!".

As green tea can be bitter, tea in the medieval period was usually prepared by pounding the leaves and making a ball with amazura (a sweetener made from grapes) or ginger, which was then left to brew in hot water. Tea, because it was expensive, also became popular with the aristocracy in medieval Japan. The calmness of tea drinking greatly appealed during the turbulent Sengoku Period (Sengoku Jidai, 1467-1568), also known as the Warring States Period when rival warlords or daimyo fought bitterly for control of Japan. The teahouse (see below), now more than ever, became a place of retreat and respite and tea drinking became especially popular with the samurai warrior class. By the 16th century, the plant was being grown across Japan, tea shops sold it in cities, towns, and villages, and just about everyone in Japanese society was drinking tea, from lowly farmers to high government officials.

Cultivation & Trade

One of the first places high-quality tea was grown was at the Kōzan-ji temple on Mt. Toganoo. It was here perhaps that it was discovered that shading the tea plants made the resulting tea less bitter, so much so, Toganoo tea became a sort of brand in itself. Uji in Yamashiro is the region best known for its tea production.

A 1680 book by Totōmi, Hyakushō denki (A Peasant's Life), gives the following advice for tea cultivation, noting the crop's versatility:

Tea is a useful thing for all people, high and low. It can be planted on the borders of dry fields, or as mountain dry fields, or in places where the soil is bad and cropping cannot be done, or within household yards, or in any open place.

(Farris, 83)

The process may be mostly mechanized today, but tea leaves require several stages of production to make them ready to drink. Some Japanese tea houses still use traditional methods. Through May, the best and greenest tips of the leaves are picked. To avoid fermentation and maintain their fresh green colour, the leaves are steamed. The steaming process lasts up to 20 seconds and was originally done using bamboo sieves held over tanks of boiling water. An alternative to steaming is to put the tea leaves in a bamboo cage held over a heated pan, but this method, known as pan-firing, was more usual in China and other Asian countries. The leaves are then spread out evenly on a heated table to dry. The leaves are tossed into the air by hand to remove any lingering moisture. To further dry out the leaves and make sure none are curled up, small groups of them are rolled on the table by hand. This stage, which can also involve a brush and grooved board, breaks down the internal cell structures increasing the flavour. The leaves should now be completely dry and have a needle-like shape, they are then baked in an oven to remove as much humidity as possible and so extend their shelf life. For matcha, the finest green tea in Japan, the leaves are additionally sorted to remove impurities, leaf veins, and stems, then chopped, filtered, and aired once again. The mass is then stored and only ground in a stone mortar to produce a very fine powder when it is to be consumed.

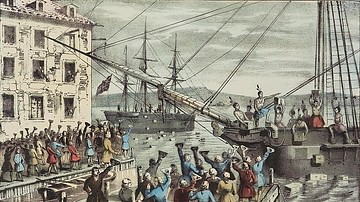

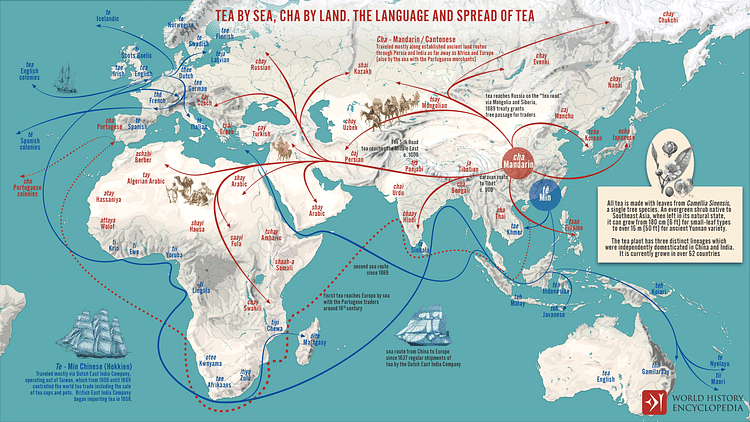

As production grew, so tea became a source of tax revenue from the 13th century. No longer merely consumed by those who grew it, tea had become big business and established itself as an integral part of Japanese culture. By the final years of the 16th century, Portuguese and Dutch traders began to show an interest in tea, and the drink was introduced into Europe around 1607. Tea cultivation spread to European colonies, notably British India. Japan, preferring to remain isolationist for much of its history, did eventually seek to trade with Europe. Echoing the innovations of Madam Clicquot-Ponsardin of Champagne fame, the first Japanese tea merchant to seek new opportunities abroad was a woman, Kei Ōura (1828-1884), who exported six tons of tea to Arabia, England, and the United States in 1853.

Tea continued to be grown successfully in the 19th century. The historian W. W. Farris suggests that the agricultural surplus of tea production was a contributing factor to Japanese industrialisation. The health benefits of drinking boiled water and the stimulant effects of tea may also have been factors in helping Japan possess the fit workforce required for long shifts in factories.

In 1875, tea cultivators began to take an interest in new methods being used in plantations in India. Motokichi Tada (1829-1896) visited Darjeeling and brought back ideas for new machinery and tea plants for replanting in Japan. Tea had become a truly global drink. Tea remains popular with Japanese growers in the 21st century, some 80,000 tons of tea are produced annually.

Tea as Art

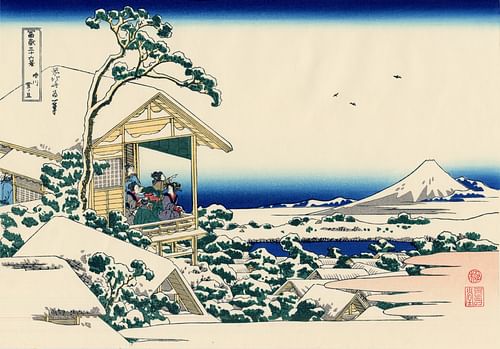

To return to medieval Japan, tea was so popular by the 13th century that specialised schools began to flourish which taught people how they should drink tea. Green tea dominated and came in two varieties, rough leaves, which were used for tea drunk after meals, and fine powder tea, which was reserved for special occasions. People drank tea in dedicated tea rooms (chashitsu) or in a garden teahouse. This house is called a sukiya, meaning 'house of the imperfect' since they were first made from very simple materials like bamboo, earth, and thatch, and sparsely furnished. They had low doors, perhaps to remind all entrants that they were equal and entering a space where there should be no rank, whatever one's status on the outside.

The teahouse may be set in its own special garden (roji) with stepping stones (tobi-ishi), evergreen trees, and heavy moss, all designed to calm the visitor before beginning the tea ceremony. Already, then, the tea drinker is being transported from the hustle and bustle of their everyday life into a calm retreat. Before entering, the visitor passes a stone lamp and basin (chōzu-bachi) in which they may cleanse their hands. Inside the small space of the hut, there is tatami floor matting. The host prepares the tea behind a sliding screen. The finest porcelain or lacquerware might be used for the tea storage jars, teapots, and cups. Tea jars often became decorative objects in themselves and so were used as permanent ornaments in the home.

With books written by experts on how to conduct oneself and appreciate tea fully, along with eulogising poems, tea drinking developed into an art form and a highly stylised ritual that has become known simply as the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Tea features in many genres of Japanese art such as literature, theatre, painting, and calligraphy.

One book that has continued to gain popularity in the 21st century is The Book of Tea, written by Kakuzo Okakura and first published in 1906. Okakura notes:

In our common parlance we speak of the man 'with no tea' in him, when he is insusceptible to the serio-comic interests of the personal drama. Again we stigmatise the untamed aesthete who, regardless of the mundane tragedy, runs riot in the springtide of emancipated emotions, as one ‘with too much tea' in him.

(4)

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

The Japanese Tea Ceremony is called chanoyu, meaning "hot water for tea", or chado or sado, meaning "way of the tea". Tea parties began as rather boisterous occasions where guests tried to guess the type of tea they were drinking, but the 15th-century shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (r. 1449-1473) put a stop to all that and made the whole thing a much more tranquil event, which offered the ruling class a perfect setting for discrete conversation on sensitive subjects.

The ceremony typifies the Japanese aesthetic principle of wabi, the value given to the appreciation of beauty and simplicity in everyday things. The application of wabi to the tea ceremony is credited to the 16th-century monk and tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), although some historians prefer Murata Shukō (aka Juko, 1422-1502), the semi-legendary Zen Buddhist monk, as the first source of inspiration. In any case, it seems several tea masters over the years helped the tea ceremony evolve.

Rikyu was master of the tea ceremonies of the warlords Oda Nobunaga (l. 1534-1582) and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598). Rikyu was more than a maker of tea, though, and became an important advisor to his masters. It is for this reason that Japanese diplomacy came to be "called the 'politics of tea' and that gave rise to the use of a tea master in political negotiations as well as in the ceremonies of rule" (Hall, 491).

Rikyu, besides instilling the aesthetic of wabi to tea drinking, also made the tea room smaller, simplified the processes, and promoted the use of carefully arranged flowers (ikebana) to create just the right atmosphere of calm. Rikyu's masters drank tea when meeting figures of importance, but they did not always listen to their tea master, it seems, for Hideyoshi famously threw an all-day tea party for 800 guests, the Great Kitano Tea Party, to celebrate his military victory in Kyushu in 1587. Hideyoshi also built two teahouses, one in the traditional rustic style and, in glaring contrast to convention, a second portable one that sparkled with exterior and interior gilding. Still, Rikyu had more success with subsequent generations as the tea ceremony gradually became more stylised and more genteel and intimate. So much so that the norm was established of drinking one's green tea in precisely three and a half sips and finishing off with a small sweet. Certain implements should be used and tasks performed in a certain order and with an economy of movement. Tea schools, the first of which were founded by Rikyu's grandson Sen Sotan (1578-1658) and descendants Soshitsu (1622-1697), Sosa (1619-1672), and Soshu (1593-1675), spread the principles of the ceremony across Japan. There were even schools specifically aimed at getting the lower classes involved, for example, the Urasenke school.

Although the tea parties slimmed down to fewer participants, the love of decorative objects related to tea never diminished. Bowls, caddies, and kettles became highly prized by collectors and featured prominently as gifts from rulers. For example, Nobunaga once rewarded Hideyoshi for capturing an enemy castle by giving him a tea kettle. Both warlords were avid collectors of tea paraphernalia.

Despite the dominance of warlords, who often limited just who could and could not participate in tea-drinking parties, the experience of drinking tea did over time recapture its original spiritual element. Tea drinking became a shared moment of calm and renewal for its participants. As the old Japanese saying goes, cha-Zen ichimi or "Zen and tea have the same flavour.". Or, as Okakura puts it, "Teaism was Taoism in disguise" (29).

Key ideals of drinking tea are wa (harmony), kei (respect), sei (purity), and jaku (elegance and tranquility). The tea ceremony is not, however, a formal event ("ceremony" is rather a poor translation) since the main idea is to relax the participants. There are, though, certain procedures to follow.

Japanese Tea Drinking Today

While not everyone may go for the full-on tea ceremony in a sukiya, there remain some points of etiquette when drinking tea in Japan, even today. The host should be doing all the preparation, not the guest. The location should be tranquil, preferably with a calming view like a landscaped garden or at least a handsome arrangement of flowers in the room. Flowers should be arranged to appear as if they are still growing wild and the opportunity to place them in a fine vase should not be missed. One wall might be adorned by a choice print or decorated scroll (jiku). The first thing is to assemble the proper equipment or chadogu. There is a brazier (furo) or hot tile (shikigawara) for heating the iron kettle (kama). There are two types of tea caddies, a silk-bag chaire for thick or stronger tea and a porcelain natsume for thin or weaker tea. One needs a bamboo whisk (chasen) for mixing powdered tea and hot water.

The highest quality green tea, as noted, is matcha. The very fine matcha powder is sprinkled and whisked into the hot water in the drinking bowls (chawan). The drink is a little frothy. An alternative is sencha, brownish loose-leaf tea that is brewed or steeped and which, being much cheaper than matcha, is more widely drunk. Matcha tends to be reserved for special occasions and the tea ceremony.

The bowls used can be of any material, but pieces with character or a history make for engaging conversation. Bowls and utensils can even be valuable antiques, but they should not be too elaborate in design as this would contradict the principle of wabi. It is also preferable that the colours complement that of the tea being served. Old bowls can even show signs of repair since this displays the quality of sabi, that is the faded beauty seen in much-loved and well-used objects. Naturally, the host serves the guests before themselves. The tea should be drunk in small sips. A full appreciation of the tea ceremony requires that the guest possesses not only a knowledge of tradition but also is aware of trends in the visual arts, architecture, garden design, flower arranging, and ceramics.

Imbued with Zen principles, the full tea ceremony is often performed for visitors to Japanese Buddhist monasteries. There are three original tea rooms still in existence, and these are listed as National Treasures of Japan; they are to be found in the Myoki-an of Yamasaki, within the Shinto shrine of Minase-gu, and at the Saiho-ji monastery in Kyoto. Besides these more formal settings, tea, is, of course, nowadays available everywhere from sushi restaurants to vending machines. Finally, a packet of quality tea is still widely given as a gift, just as it was by those who started off Japan's love of tea, the Buddhist monks of the 8th century.