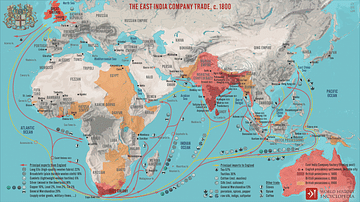

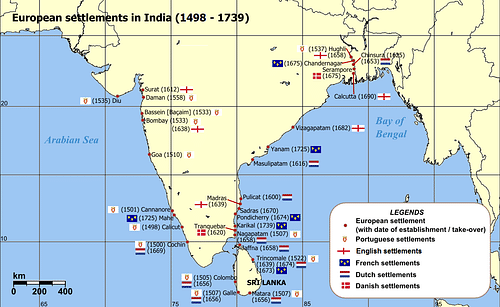

In the early 17th century, the Dutch and English East India Companies turned their eyes towards India, as part of their grand schemes to develop extensive trade networks across the Indian and China Seas. They were faced with two significant challenges: 1) gaining the favor of the Mughals who now controlled most of North India and, 2) pushing out the Portuguese who were well entrenched along the west coast.

The Mughals

By 1600, the Muslim Mughals under Akbar the Great (r. 1556–1605) ruled most of India. The Mughals had arrived on the subcontinent about the same time as the Portuguese. Akbar was a ‘workaholic’ who seldom slept more than three hours a night and personally oversaw the administration of his vast country. He built his empire by conciliating conquered rulers through marriage and diplomacy, winning him the support of even his non-Muslim subjects.

When Akbar died, Jahangir became the fourth Mughal emperor, ruling from 1605 until 1627. He was a largely ineffective leader, addicted to opium and subject to court intrigues. Under his tenure ‘the number of unproductive, timeserving officers mushroomed, as did corruption’ (Heitzman, 23). Jahangir was far less impartial than Akbar and supported mass conversions to Islam. He married a Persian princess, and his court became filled with Persian artists, scholars and writers who found asylum in the Mughal court.

Jahangir was replaced by his son, Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658), who had a great passion for building, exemplified by the Taj Mahal. He also strongly supported literature, painting and calligraphy and he probably had the largest collection of jewels in the world. This opulent lifestyle was not without consequences as it greatly strapped the Mughal Empire’s economy at a time when resources were shrinking.

The last of the great Mughal leaders was Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), who took power by killing all his brothers and imprisoning his father Shah Jahan. Under Aurangzeb’s reign, the empire became the world’s largest economy, holding almost a quarter of the world’s gross domestic product, although it was at the same time failing. ‘The bureaucracy had grown bloated and excessively corrupt, and the huge and unwieldy army demonstrated outdated weaponry and tactics" (Heitzman, 24). When Aurangzeb died in 1707, the great Mughal Empire that had controlled most of India for 180 years quickly fell apart and dissolved into many smaller independent states that were picked off by the English.

England’s Entry into India

The first expedition of the English East India Company (EEIC) to India was led by William Hawkyns, who landed the Hector at Surat on 24 August 1608. Hawkyns proceeded to emperor Jahangir’s court at Agra, where he hoped to secure a trading agreement. This took some time, as the emperor so greatly enjoyed the company of Hawkyns that he detained him for three years before granting a farman (licence) to build a factory. While at court, Hawkyns was provided with a handsome salary and a wife.

In 1612, Thomas Best was sent to Surat from England with a fleet of four ships – the Red Dragon, Hosiander, James and Solomon. Soon after they arrived, a squadron of four Portuguese galleons and 16 barks confronted them and a pitched battle ensued over a three-day period. Three of the galleons were grounded and one was sunk, forcing the Portuguese to withdraw. The whole affair was witnessed by thousands of people on the shore and so impressed the sardar (governor) of Gujarat that he convinced the emperor that henceforth he should favour the English over the Portuguese. This put English trade on a permanent footing in India.

In 1615, Thomas Roe was sent to India as ambassador of King James I, and through lavish gifts and flattery to emperor Jahangir he was able to obtain a farman to trade and establish factories all across the Mughal Empire. Jahangir was not willing to give the king exclusive trading rights but did allow the English the right to compete with the traditional traders. The EEIC also convinced the Vijayanagara Empire of the south to allow them to open a factory in Madras. The English then began to establish trading posts up and down the coasts of India, and large English communities were established in the three major trading towns of Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai) and Bombay (Mumbai).

Early Dutch Dispersal into India

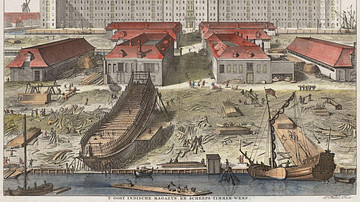

The first Dutch merchant sent to India by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; VOC) was David Van Deynssen who was sent to Surat in 1606. Unfortunately, his mission turned out to be a failure, as the Portuguese succeeded in setting the Mughal authorities against him. After being tortured by the latter and repeatedly threatened he committed suicide, leaving all his merchandise in their hands.

The VOC spent the next ten years trying to get compensation for Van Deynssen’s belongings worth about 20,000 guilders. An opportunity appeared in 1615, when the Mughals offered to return the goods if the Dutch would give them naval support in their war against the Portuguese. A factor named Ravensteyn was dispatched overland from Masulipatam (Machilipatnam) to Surat to receive the goods, but by the time he got there the Mughals and Portuguese had made peace and Ravensteyn returned empty-handed.

Next, the director general of the VOC dispatched Pieter Van den Broecke to Surat in August 1616. He too was initially frustrated, but finally in 1618 with the support of the local Gujarat merchants, Emperor Jahangir issued a generous farman allowing the Dutch to trade in Surat. This agreement was renewed 28 times between 1618 and 1729.

The East India Companies Spread out from Surat

Surat held most of the EEIC’s early attention in India, but its importance declined dramatically when a protracted drought in the 1630s affected all of western India. As an eyewitness described:

When wee came into the cytty of Suratt, we hardly could see anie living persons, where heretofore was thousands; and ther is so great a stanch of dead persons that the sound people that came into the town were with the smell infected …

(Barrow, 13)

Surat did manage to recover, but the EEIC gradually shifted its focus towards the west coast of India to Bombay, then Madras on the eastern Coromandel Coast and finally Calcutta in Bengal.

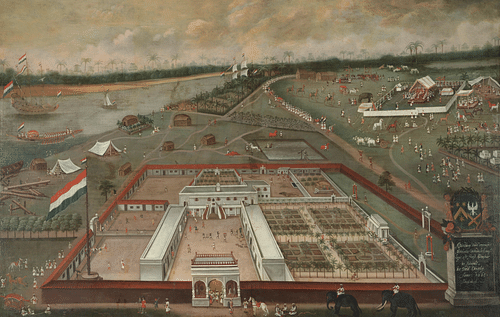

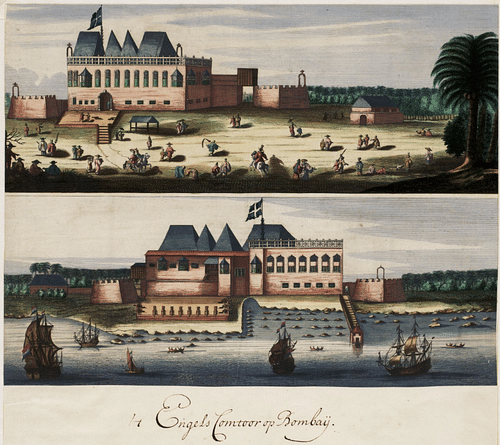

Bombay was received as a gift from the Portuguese to the English king, Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), as a part of the dowry arrangement in his marriage to Catherine of Braganza. The EEIC moved its headquarters to Bombay in 1687, when local political pressure at Surat became too intense and required a move. The local authorities were becoming increasingly unhappy with the EEIC who had begun seizing ships of their European competitors and therefore damaging Mughal trade. The English also feared the other regional power, the Maratha Confederacy, which had sacked Surat on two occasions.

The VOC began establishing trading posts along the Coromandel Coast in the early 17th century. Factories were set up in 1600 at Palecatte (Pulicat) and in 1615 at Masulipatam. A factory at Negapatam (Nagapattinam) was captured from the Portuguese in 1658. The VOC tussled with the Portuguese and local authorities to hold these settlements and as a result, most of their trade became organized around fortresses and strongholds. The VOC built Fort Geldria in Pulicat which became their Coromandel Coast headquarters and served as the home of the VOC governor for the Coromandel until 1690.

The first settlement of the EEIC on the Coromandel Coast was at Masulipatam in 1611, but they moved their settlement south to Madras in 1639 and built Fort St George, to escape the ongoing warfare between the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda and the Mughals. Madras was selected more for location than convenience, as it did not have a natural harbour and trade was conducted by catamarans between the land and anchored ships. In 1658 all other English settlements on the Coromandel Coast were made subordinate to Fort St George and by the 1670s, Madras had eclipsed the amount of trade in Surat.

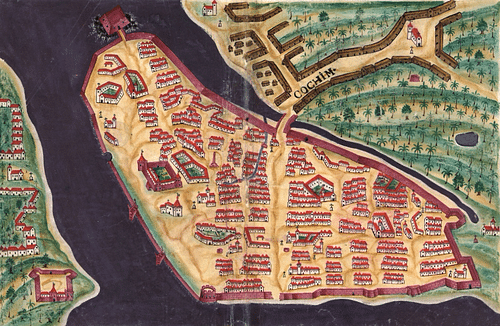

Both the Dutch and English began trading in Bengal in the early 1600s, but it wasn’t until the early 1630s that the local Mughal ruler granted the European companies full trade concessions. The Bengal governor Shah Shuja permitted the English and Dutch to trade without any customs duties in lieu of annual payments to his government. A trading post was established by the Dutch first in Calcutta and from there the VOC took almost the entire Malabar Coast from the Portuguese, driving them forever from the west coast of India by 1663. They established their own series of fortifications along the coast, with their headquarters set up in Cochin. The EEIC established its first factories at Balasore in 1633, Kasim Bazar (Cossimbazar) in 1658, Hughli in 1658, Dhaka in 1668 and Calcutta in 1690.

Bengal would become the centre of both the VOC and EEIC trade in India. The Bengal Subah province of the Mughal Empire was its wealthiest state and became the worldwide trade centre for muslin and silk. In addition, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silk and cotton. Saltpetre was also shipped to Europe from Bengal; opium was sold in Indonesia; raw silk to Japan and Europe; cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia and Japan; cotton to the Americas and all across the Indian Ocean. Bengal came to account for about 40% of the Dutch imports from Asia, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silk.

French Competition

In 1668, the first French factory was established at Surat in India, under the auspices of the Compagnie Française des Indes Orientales established by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister to King Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715). In 1674, Pondicherry (Puducherry), lying about 85 miles (137 kilometres) south of and not far from the EEIC’s trading centre at Madras on the Coromandel Coast, became the centre of French India.

From the beginning, the French, found themselves in constant conflict with the Dutch and the English. The jealous VOC even drove them out in 1693, but the company returned in 1699 and for the next 100 years Pondicherry served as the Indian capital of the French, who eventually built factories in Surat, Chandernagor (French name; formerly Chandernagore, now Chandannagar), Calicut, Dhaka, Patna, Kasim Bazar, Balasore and Jodia.

The most famous governor of French India was Joseph François Dupleix, who tried to build a French territorial empire in India even though the French government was not particularly interested in provoking the British. Dupleix’s army came to control the area between Hyderabad and Cape Comorin but was subjected to constant political intrigues and military skirmishes with the English. The ambition of Dupleix to create a French empire in India was dashed when British Major-General Robert Clive arrived in India in 1744, took possession of Bengal and then smashed the French forces. Dupleix was summarily recalled to France and dismissed in 1754.

VOC Loses Steam

The overall profits of the VOC peaked in the 1670s and then began a slow, gradual decline. It was forced to leave Formosa in 1663 and as a result it could no longer trade Chinese silk for the Japanese gold that they had traditionally used to acquire Asian goods. The Dutch tried to focus on the Bengal silk market, but the profits were not nearly as high. From 1675 to 1683 the VOC and the EEIC got into a price war that brought both companies near bankruptcy. The VOC got a bit of a boost in 1685, when it was able to force the British competition out of Bantam, Java, but this was greatly offset by a Japanese decision to limit the export of gold and silver in that year, depriving the Dutch completely of their key source of precious metals. They faced a rebellion in Java from 1741 to 1743, after a massacre of 10,000 local Chinese in Batavia. The competition from the French and also the Danes in the late 17th century, put their Indian holdings at risk. The Dutch strongholds along the Malabar Coast and the Persian Gulf were finally lost in the 18th century, after the British greatly decimated their East Asian navy during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War from 1780 to 1784.

The EEIC Takes Full Control of India

In 1686, the EEIC felt the time was right to embark on a direct war with the now fading Mughal Empire to obtain broad trading privileges across the entire continent and more specifically to get permission to build a fortress in Bengal. A fortress in Bengal was seen as a critical step to protect the company’s burgeoning trade there from the Dutch and interlopers.

The First Anglo-Mughal War (1686–1690) began at the Hugli River at Calcutta and ultimately was fought on both coasts. Often called ‘Child’s War’, it was driven by one of the company’s major stockholders, Josiah Child, and proved to be a great embarrassment to the English nation. Twelve British battleships were involved, and several battles raged across the continent including a siege of Bombay and burning of the city of Balasore. The British navy blockaded the Mughal ports on the western coast and attacked its army on land. Several major cities were significantly damaged in the fray including Bombay, Madras, Calcutta and Chittagong.

A pivotal point in the conflict came when the English confiscated a convoy of ships carrying a grain shipment to Yakut Khan, a regional leader who was allied with the Mughals but had stayed out of the fight. In response, Sidi Yakur landed a force at Bombay and began a siege of the city that lasted almost a year and a half. The war was finally ended in 1690, when the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb issued a farman and allowed the English to build a fortress at Calcutta, but not before requiring them to pay a huge fine, return seized property and comply with a lot of other conditions.

The reaction in England to the war was one of vehement disgust. Barrow quotes a pamphleteer who described how the war had ruined the good name of England: ‘Thus has the English Nation be made to stink in the Nostrils of that people; when before, from the time we set footing on that Golden Shoar, we were the most loved and esteemed of all Europeans." (18)

Traders to Rulers

As the 18th century progressed and the VOC were forced to abandon India, the time was right for the EEIC to carry its invasion of India to its final conclusion and make the transition from merchants to rulers. The company’s shift to ruler began in Bengal in 1756 when after decades of benevolent rule by the Mughals, Siraj ud-Daulah became the nawab (governor) and decided to exert his authority. He demanded exorbitant amounts of cash from the East India Company and launched an attack on the English fortifications in Calcutta. These he easily took, along with 146 prisoners who were forced to spend the night in the fort’s prison called the ‘Black Hole’. Many died in the heat and humidity, enraging the British colonial community.

A force was sent from Madras to retake the city that was led by Robert Clive, who quickly recaptured it and put Siraj ud-Daulah to death. A period of turmoil and court intrigue then followed until the Treaty of Allahabad was signed in 1765 with the Mughal emperor. This treaty allowed the company to collect revenue in the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orrisa for an annual stipend and in essence made the company a sovereign state.

Many other wars followed that ultimately gave the British control of most of India. Beginning in the 1740s, the company fought at least one major war a decade until about 1850. The Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–1799) were fought over southern India, the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818) over central India, and the final Sikh Wars (1845–1849) over the Punjab of northern India.

End of EEIC Rule of India

The EEIC ruled India until 1858, when the Indian Rebellion led the British government to take over control of the country. At about the same time as the Opium Wars, the company began witnessing a rapidly increasing amount of insurgence in its Indian territories. The company’s conquest of the subcontinent during the 18th and early 19th centuries had left many scars. Many of the rebels were Indians within the EEIC’s own army which by this time had grown to over 200,000, of whom 80% were Indian recruits. The rebels caught the British off guard and managed to kill many British soldiers, civilians and Indians loyal to the company. In retaliation, the company brutally murdered thousands of locals, both rebels and anyone thought to be sympathetic to the rebellion. It ended in Delhi where 1400 were murdered. As quoted by William Dalrymple:

'The orders went out to shoot every soul,’ recorded Edward Vibart, a nineteen year-old British officer. ‘It was literally murder … I have seen many bloody and awful sights lately but such a one as I witnessed yesterday, I pray I never see again. The women were all spared but their screams, on seeing their husbands and sons butchered, were most painful … Heaven knows I feel no pity, but when some old grey bearded man is brought and shot before your very eyes, hard must be that man’s heart I think who can look on with indifference …' (7)

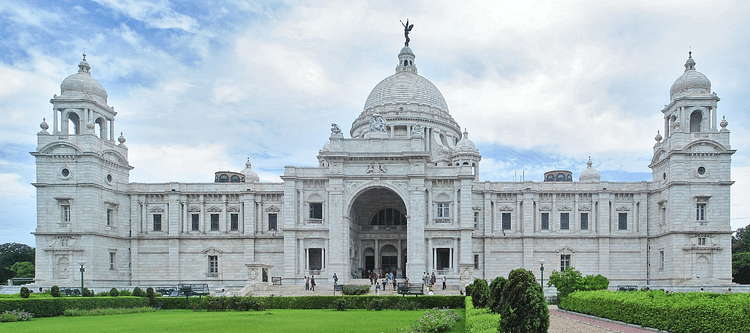

In the wake of this bloody uprising, the British government effectively abolished the EEIC in 1858, taking away all its administrative and taxing powers. The Crown assumed control of all its territories and armed forces. Thus began the British Raj and the direct British colonial rule over India which continued until India was given its independence in 1947.