Argula von Grumbach (née von Stauff, l. 1490 to c. 1564) was a Bavarian theologian, writer, and reformer, who became a controversial figure after her 1523 letter To the University of Ingolstadt protesting the arrest of a young scholar for teaching Lutheran precepts. She suffered for her convictions but remained committed to the Reformation until her death.

Von Grumbach was well-educated and had read the Bible in a German translation before Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) began what would be known as the Protestant Reformation in 1517. She converted to the so-called 'new teachings' around 1520 or 1522 after reading the works of Luther's right-hand man, Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), and became a public figure in 1523 after her letter To the University of Ingolstadt was published. She continued to publish for the next year until the German Peasants' War (1524-1525), which many associated with Luther's teachings, may have caused her to pause, though she continued to write private letters.

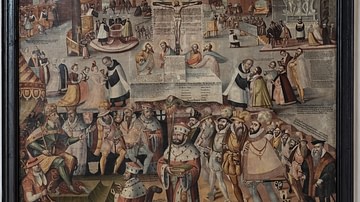

She maintained a close correspondence with Luther, Melanchthon, and other reformers including Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551) but was never publicly included in their activism because she was a woman. Her writings were denounced by Catholic authorities and criticized by others for the same reason, and her first marriage became strained due to her notoriety. Even so, she continued to travel and advocate for reform throughout her life at such great personal cost that she was included in the 1572 edition of the History of Martyrs by Luther's former student Ludwig Rabus (l. 1524-1592), even though there is no evidence she died for her faith.

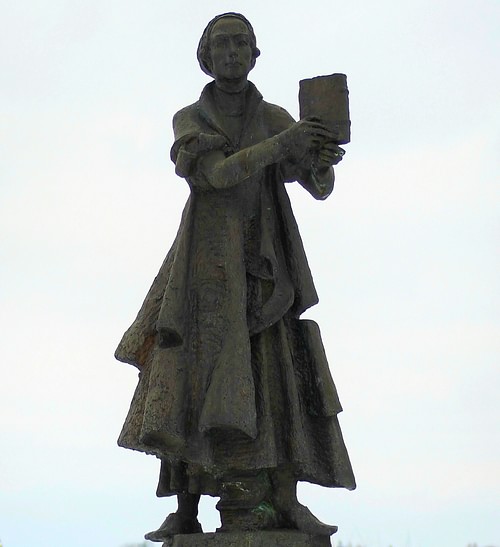

As with many of the now-famous women of the Protestant Reformation, her eight published letters between 1523 and 1524 were ignored by historians until the modern era, and von Grumbach only began receiving serious attention in the late 20th century. Today, she is recognized as an important figure in the early years of the Reformation as an advocate for women's equality.

Early Life & Conversion

Von Grumbach's year of birth is given as early as 1490 but has also been cited as 1492 or even 1493, and her death date is equally uncertain ranging from 1554 to 1564 or even 1568. The dates 1490 to c. 1564 are commonly accepted but by no means certain. She came from the noble von Stauff family of Bavaria, and her father ignored the prevailing belief that educating girls was a waste of time (or would even confuse them and lead them into sin) and had her privately educated along with her siblings. The family was politically connected and held their traditional baronial seat at Ehrenfeis Castle in Regensburg.

When she was ten years old, she was given a copy of the Koberger Bible (published in 1483), a German translation of the Latin Vulgate. Although the Catholic Church prohibited translations of the Bible into the vernacular, various clergy had done so anyway, going back to John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) of England and Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415) of Bohemia. The fact that her father gave her a Bible in the vernacular strongly suggests the family was not orthodox, which no doubt contributed to her later receptivity to the Reformation's vision.

When she was around sixteen years old, she was sent to the royal court at Munich to attend Duchess Kunigunde of Bavaria (l. 1465-1520) as a lady-in-waiting. Kunigunde was well-educated and spiritually-minded and seems to have encouraged Bible study and discussion of scripture. She also invited various ministers and theologians to her court where von Grumbach met Johann von Staupitz (l. c. 1460-1524), mentor to Martin Luther.

In 1509, both her parents died of the plague, and she was adopted by her uncle, Hieronymous von Stauff, who was executed in 1516 accused of political intrigue. Later that year, she married Friedrich von Grumbach (d. 1530), also of a prestigious Bavarian family, who held an administrative post at Dietfurt. The couple settled in Dietfurt and would have four children: George, Hans Georg, Gottfried, and Apollonia.

Between 1516 and c. 1522 the family is presumed to have been uniformly Catholic, but after Luther's and Melanchthon's works began to circulate around 1520, von Grumbach converted to the Reformed vision of Christianity and insisted her children be raised according to its precepts. This dating is based on Argula von Grumbach's To the University of Ingolstadt in 1523, by which time she was already committed to the Protestant cause. Her husband remained Catholic, which, according to her later writings, caused significant tension in the marriage.

To the University of Ingolstadt

As Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms in 1521 gained him more adherents, his vision became especially attractive to university students. At the University of Ingolstadt, the Catholic theologian Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543), who had denounced and debated Luther at Leipzig in 1519, prohibited the teaching or dissemination of Lutheran theology, condemning it as heresy. A young student, Arsacius Seehofer (l. c. 1504 to c. 1539) was enrolled at Ingolstadt in 1518 but traveled to Wittenberg, the seat of Luther's Reformation, c. 1521 to study with Melanchthon. When he returned to Ingolstadt in 1522, he was warned by Eck against introducing any Lutheran concepts to the student body.

As a young member of the faculty (around 18 years old) in the spring of 1523, Seehofer ignored Eck’s warning and presented a lecture on Melanchthon's theology. He was censured, and his apartment was searched for heretical works. 17 Lutheran texts were seized, and Seehofer was dismissed from the school, arrested, and threatened with execution by burning at the stake if he did not renounce Lutheran theology. Seehofer seems to have refused at first, but his father intervened and had the case moved from the ecclesiastical court to the secular, which agreed to waive the prospect of capital punishment if Seehofer recanted, which he then did. He was still expelled from university, however, and sent to Ettal Abbey where he remained a prisoner until 1524.

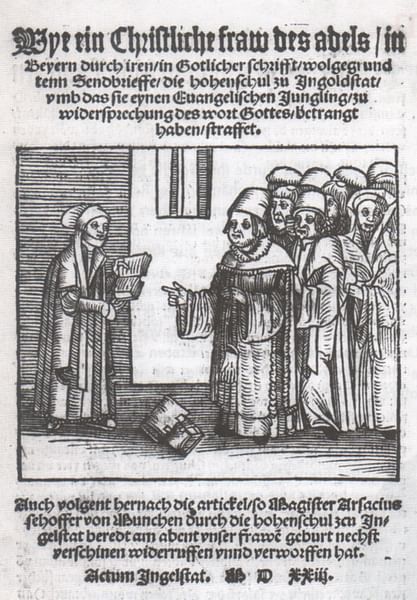

Von Grumbach was incensed when no one came to Seehofer's defense and so wrote her now-famous letter To the University of Ingolstadt demanding the faculty explain what Seehofer was guilty of and, by extension, why the works of Luther and Melanchthon should be considered heretical when they adhered solely to scripture. Scholar Kirsi Stjerna comments:

Argula was compelled to action by God and by the injustice she witnessed. She founded her arguments on the primacy of the Scriptures, supporting her case with over 80 quotations and clever rhetoric. She may have been inspired by Luther's words about the necessity for women to preach the gospel when men are silent. She boldly demanded that the university men should not only listen to but also respond to her personally. Neither her lay status nor her gender nor her lack of Latin skills posed any impediment with her. With a Scripture-based authority and Christian moral duty to intervene when a publicly funded university was culpable of misconduct, she was outraged. (76-77)

Eck and the rest of the faculty ignored her letter, and Seehofer remained a prisoner at Ettal Abbey, so she had the work published. It had previously circulated around town in the fall of 1523 in hand-written copies until von Grumbach's friend (and fellow reformer) Andreas Osiander (l. 1498-1552) suggested it be formally published and wrote a preface to the work, which became a bestseller, going through 14 editions in only two months. Encouraged by its initial success, she then wrote other letters, now addressed to nobility in the region, citing scripture and advocating for their support of the Reformation.

Married Life & Persecution

Seehofer was released in 1524 and, backtracking on his earlier recantation, took up the cause again, eventually becoming a Protestant preacher and teacher. It is unclear whether von Grumbach's letter or Seehofer's connections led to his freedom, but the popularity of her letter seems to suggest it exerted some influence if only in embarrassing the authorities in that a woman had shown herself as well-versed in scripture as they claimed to be. Her other letters had, by this time, also been published (some without her knowledge or consent) and these pamphlets circulated throughout the region in numbers exceeding 30,000. By the fall of 1524, she was a bestselling author and controversial public figure.

Bavaria was still a largely Catholic region, and von Grumbach was in the minority, publicly supporting Luther's cause (though she never identified herself as a Lutheran, only as a Christian), and so she could have been arrested on charges of heresy. It seems she was not because of her social standing as a noblewoman but also because the authorities had learned, after persecuting Luther, that trying to suppress a popular figure only led to greater support for their cause. Further, the German Peasants' War had begun, and people, in general, had greater worries than a response to von Grumbach's works. It has also been noted that, although she wrote in defense of Luther and Melanchthon, she cited only scripture, not their works.

Since the authorities could not attack her directly, they went after her husband, dismissing him from his administrative post. It has been suggested, either before or after his dismissal, that he was encouraged by colleagues and superiors to break his wife's hands, cut off her fingers, and that no charges would be brought should she be murdered, though these claims have been challenged. If these suggestions were made, Friedrich ignored them, but according to von Grumbach's letters, he "did all he could to persecute the Christ in her" (Stjerna, 79), though what form this took is unclear.

After the publication of her letter to Ingolstadt, one member of the faculty, a Professor Hauer, denounced her publicly in sermons as a "heretical bitch," "shameless whore," "female desperado," and "daughter of Eve," and these sentiments were echoed by others. After her husband lost his job, the family was banned from Dietfurt and may have moved to Lenting or some nearby village. Friedrich could not find work, and von Grumbach pawned jewelry repeatedly to pay debts and keep the home provisioned. Although she was admired by Protestant reformers, including Luther, there is no evidence any helped her financially or defended her publicly.

Luther & von Grumbach

Friedrich died in 1530, by which time her children were mostly grown, and she traveled on her own to meet Luther at Coburg when he stayed behind while Melanchthon and others went on to the Diet at Augsburg. Luther's personal writings express great regard for von Grumbach, but his published writings never mention her, even when he is addressing issues such as Seehofer's arrest and imprisonment. He seems to have benefited personally from their association as she was a noble Bavarian. Scholar Lyndal Roper notes:

It was doubtless her social status as a member of the noble Staufen family that enabled her to become Luther's friend – she belonged to the social group Luther had always cultivated – [but] the world of intellectual equality between men and women that she had dared to imagine did not come to pass. She was derided by the university and mocked by men who thought her actions and behavior inappropriate to a woman. (407)

Luther, also, seems to have felt it inappropriate to publicly acknowledge and support a woman presuming to teach men, as this was prohibited by scripture, notably by the passage in I Timothy 2:12 ("I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent"). Von Grumbach, however, maintained her right to teach and write in accordance with a concept Luther himself advocated, the priesthood of all believers, which held that anyone with sincere Christian beliefs was equal to all others, dismissing an ecclesiastical hierarchy or formal education or, in von Grumbach's view, one's sex.

Von Grumbach, in fact, cites "a school of women" supporting her, even though it is clear she acted and wrote alone, and seems to be referencing contemporaries, not only female figures from the Bible. Who these women might have been who "are able and better read than I am" (Stjerna, 78) is unknown since many of von Grumbach's own family disowned her, but there were many women active in Reformation efforts at this same time including Marie Dentiere (l. c. 1495-1561) in Geneva, Katharina Schutz Zell (l. 1497-1562) in Strasbourg, Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1562) in France and Luther's own wife, Katharina von Bora (l. 1499-1552), in Germany.

These women, and many others, advanced the Reformation in its early years but were not publicly acknowledged by their male counterparts at the time. Luther and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) both had great respect for their wives and, privately, approved of their efforts but still publicly maintained that women were subordinate to men in accordance with scripture. When von Grumbach tried to arrange a meeting between Melanchthon of the Lutherans and Bucer of the Zwinglians at Augsburg in 1530, trying to reconcile their differences over the rite of the Last Supper, she was dismissed as a woman, though her overtures would have been welcomed if she had been a man, as this same reconciliation had been attempted a year earlier at the Colloquy of Marburg.

The attacks made on von Grumbach, whatever shape they took, finally focused on the fact she was a woman presuming to teach men. One of the best-known attacks came from one Johann of Landshut in 1524, who satirized her in a poem, claiming she should stop pretending at men's business and return to spinning wool while also suggesting it was only her lust for Luther that drew her to the movement. Von Grumbach answered this poem with one of her own, but there is no evidence that Luther or any other contributed to her defense.

Conclusion

Von Grumbach married for a second time in 1533 to Count von Schlick, who supported the Reformation, but he died in 1535. She outlived three of her four children, as George and Apollonia died in 1539 and Hans Georg in 1544. Still, she maintained her faith, and as late as 1563, she is referenced as having been imprisoned for disturbing the peace by "circulating Protestant books, holding private house services, and officiating at gravesite funerals" (Stjerna, 82). Although known to history for her eight published letters between 1523 and 1524, public records and the letters of others make clear she remained an activist throughout her life and embodied the spirit of early reform, which held out hope for women's equality. Stjerna writes:

Argula was born at the right moment in history, in the window of opportunity for lay pamphlet writing, before such opportunities became more controlled. Argula, and Katharina Schütz Zell, represent what "could have been" for Protestant women in the sixteenth century and more generally. Her story also demonstrates the impediments women writers and teachers faced. She embodied the hopes of an emancipated lay person, and more specifically, of a lay woman. She embodied the zeal of the early evangelicals as she spoke out of conviction and confession, as a Christian, as a Bible teacher, and as a defender of people's religious rights, offering a lens to Scripture that could have radical social as well as theological ramifications. Contained within her actions and her words were potential repercussions for the emancipation of women and the rebellion of the suppressed peoples, such as the peasants. (84)

Although her letters helped spread the Reformation in Germany, and she was privately admired by her better-known contemporaries in the movement, von Grumbach's works were forgotten after her death. The events of her last years, in fact, are obscure, and her gravesite unknown. Like many other female reformers, she was eclipsed in history by the men of the Reformation until the late 19th and the early 20th century, although scholarly interest in her work has only been pursued in the last 30 years. Today she is frequently cited along with other women of her time as a proto-feminist and activist, which she would probably agree with, but would no doubt be more comfortable with the term 'Christian' as she understood it to mean one in whom the true spirit of Christ lives.